Diversifying Canadian exports

Canada is a trading nation: in 2018, Canadian exports and imports of goods and services totalled $1.5 trillion, placing the share of trade in the economy at 66%. The Canadian economy, and by extension Canadians, gain from this trade in many ways, with the growth of trade linked to higher incomes and living standards (State of Trade, 2012). However, the large share of trade in the Canadian economy also raises Canada’s exposure to external shocks. This exposure can be mitigated through trade diversification.

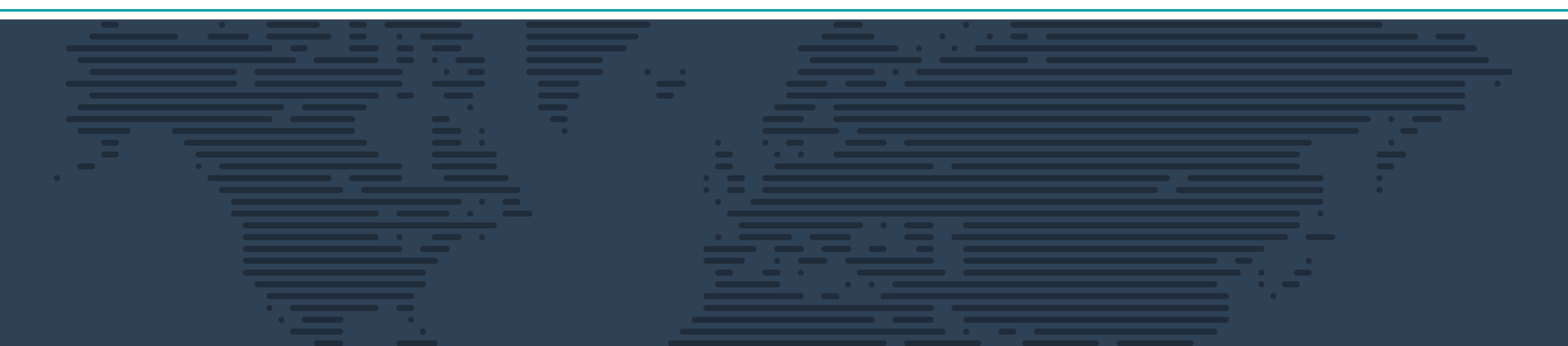

There are several dimensions to trade diversification, with geographic and product diversification being the two most commonly thought of, and usually more so with regard to a country’s exports than with imports. Geographic diversification refers to the spread of destination markets for a country’s exports, while product diversification applies to the range of products being exported. Other dimensions include regional diversification (for instance, provincial spread of Canadian exporters), type of exporter (small, medium, and large enterprises), and diversity in ownership or control of an exporting firm, with women ownership and Indigenous ownership being two facets of this diversification dimension. This section of the State of Trade report presents research by the Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) and which shows that the first two dimensions (geographic and product) are important for mitigating Canada’s vulnerability to external shocks, but are not the only dimensions of trade diversification.

Chapter 3.1

What does trade diversification mean?

At a

glance

Long description

| Dimensions of Trade Diversification |

|---|

| Geographic |

| Product |

| Region |

| Exporter size |

| Ownership |

| Importance of diversification |

|---|

| Geographic and product diversification lets Canada hedge risks and allow Canadian businesses to access opportunities in fast growing markets |

| Ownership diversification spreads gains of trade across Canada to all Canadians |

Long description

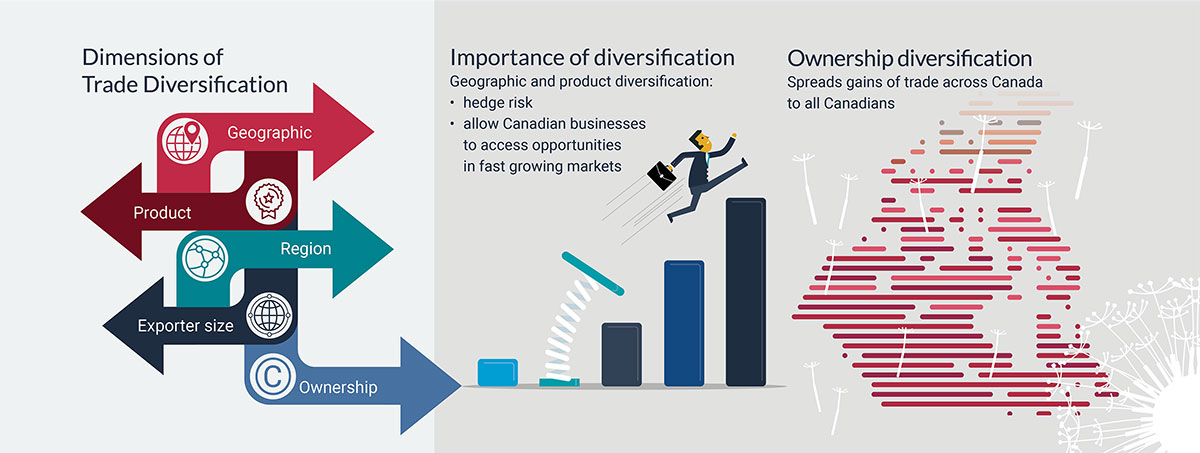

| 2025 Target |

|---|

| Expand Canada's overseas exports by 50% by 2025 |

| Canadian exports are geographically concentrated | |

|---|---|

| Country | Geographic Concentration |

| Canada | Concentrated |

| Mexico | Concentrated |

| Jamaica | Moderate |

| Mauritania | Moderate |

| U.S. | Diverse |

| U.K. | Diverse |

| France | Diverse |

| Germany | Diverse |

| Norway | Diverse |

| Sweden | Diverse |

| Australia | Diverse |

| New Zealand | Diverse |

Why is export

diversification important?

Trade diversification, or export diversification more specifically, is important because it helps mitigate a country’s exposure to shocks from abroad. Additionally, it allows Canadian exporters to take advantage of opportunities in new and expanding markets. Exactly how this is accomplished depends on the dimension of diversification considered.

Geographic diversification of exports helps hedge risks related to a particular export market; these risks can include, but are not limited to, political risks such as trade protectionist policies, country-specific economic shocks, and exchange rate volatility.Footnote 16 It is important to note that, much like using diversification to limit risk in portfolio investment, diversification will only mitigate unsystematic risk. In the case of geographic export diversification, spreading exports across a wide range of markets will limit an exporting country’s risk to specific events or actions in individual markets; it will not help mitigate systematic risk, i.e. risks that affect multiple markets at once. For example, in the global economic and financial crisis of 2007–2009, the vast majority of developed countries saw their economies contract, thus lowering their demand for imports. Following the crisis, Canadian goods and services exports saw a significant decline, dropping 21% from 2008 to 2009. The contraction in Canadian exports matched the global trend in declining trade at the time,Footnote 17 and greater geographic diversification of Canadian exports would likely have been of little help in mitigating Canada’s vulnerability to this systematic risk.

A greater geographic diversification of exports can also be beneficial to the Canadian economy in ensuring that Canadian exporters do not miss out on opportunities in emerging, fast-growing economies, and that Canadian exports are not overly focused on slower growing developed economies. Accessing new and fast-growing markets also provides a feedback effect of further diversifying Canadian exports; OCE research shows that entering fast-growing markets earlier gives an additional positive boost to exports in those markets. This research is discussed further in part two of this chapter.

Product diversification can also help abate risks from external shocks. In this case, exporting a wider range of products limits the exporting country’s exposure to risks from fluctuations in prices and shocks to demand or supply of specific products or services.Footnote 18 Once again, it is important to note this diversification is only a hedge against unsystematic risk, i.e. the risk of a negative shock to a specific or small subset of exported products.

Having a diverse range of export products and services also shields an exporting country from a problem often referred to as “Dutch disease”. This problem occurs when a single commodity makes up a large portion of a country’s exports. A sharp increase in external demand for the product may appreciate the country’s currency, making imports relatively cheaper and exports more expensive—both of which reduce the competitiveness of other industries and further concentrates the economy on the dominant export.

A final benefit of product diversification, again akin to geographic diversification, is that it allows greater access to new and fast-growing markets, but in this case product markets as opposed to geographic markets. The wider range of products exported will allow a country to take advantage of faster growing product sectors.

Diversification in the regional distribution of exporters, type of exporter, and ownership of exporting firms is important because these dimensions of diversification spread the gains from trade across Canada and among Canadians. For instance, firms that export have been shown to be more productive and, on average, pay higher wages than non-exporting firms (State of Trade, 2012). Having exporting firms dispersed across Canadian regions and communities will help economic benefits and opportunities distribute evenly throughout the country. Additionally, lowering barriers to exporting for small and medium firms will help them grow and prosper, while providing support for women-owned or Indigenous-owned enterprises to export will make the gains from trade more inclusive.

These different dimensions of diversification do not stand alone but intersect: each is related to the others and bolster their mutual benefits. For example, if a specific country impose a tariff on a specific Canadian export, the damage could be reduced by both geographic and product diversification. That said, it may not always be possible to achieve perfect diversification; every country has comparative advantages in producing certain products and services, and it is often economically efficient to specialize in producing some goods and services while importing those for which other countries have their own comparative advantages. Further, some regions of Canada will specialize in particular sectors, and the demand for these products may be stronger in some markets than others.

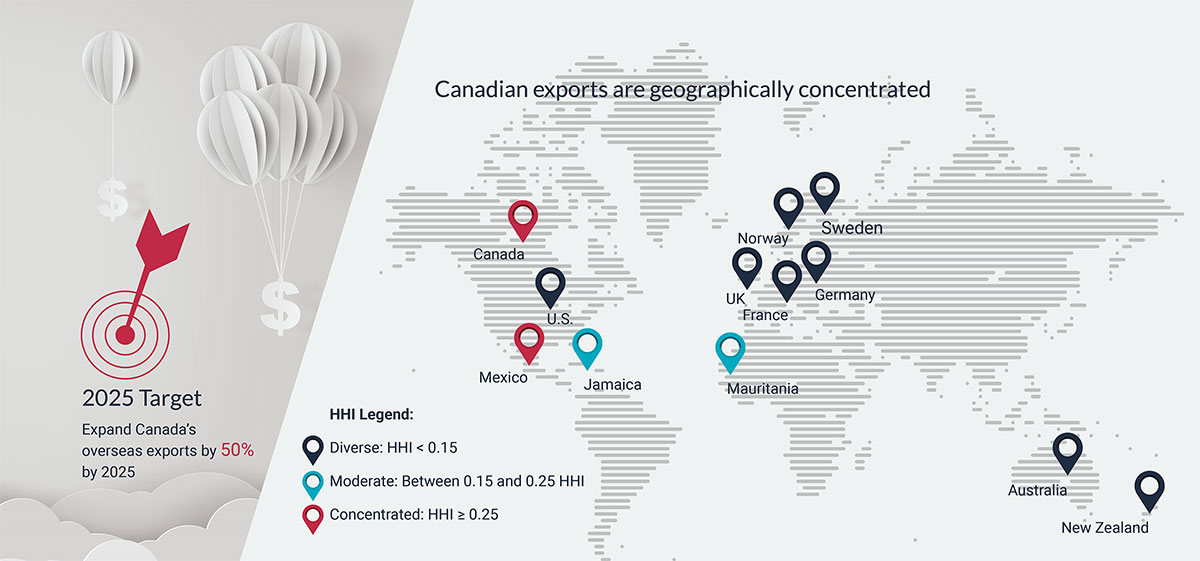

Box 1: Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)

Where Si is the share of nominal exports at time t and i can be market or product.

This index constructs a score from zero to one. The closer the index is to one, the more concentrated is Canada’s trade. For example, if Canada only traded with one country, the share of exports heading to that country would be 1 and the index would equal 1.0. Alternatively, if Canada’s trade was divided evenly between 100 different countries, the index would equal 0.01.

- Statistics Canada provides the following internationally accepted guidelines:

- Diversified export products or markets: HHI < 0.15

- Moderately concentrated products or markets: 0.15 ≤ HHI < 0.25

- Highly concentrated products or markets: HHI ≥ 0.25

Are Canadian exports diversified?

With the benefits of diversification established, an important question is: how diversified are Canadian exports? This can be asked in regard to all dimensions of diversification, but for simplicity we will first look at the well-established concepts of geographic and product diversification and return to the other dimensions of diversification in part three of this chapter.

To assess the level of diversification in Canada’s trade requires a proper measure. While there are many ways one can measure diversification, the most common measure, which will be used here, is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). This measure of diversification is used by Statistics Canada, the United Nations, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Box 1 provides more details on the HHI.

Using this measure we find that, on a geographic basis, Canadian merchandise exports are highly concentrated (with an HHI of 0.57 in 2018). Scarffe (2019a) finds that Canada’s exports are the fourth most concentrated by destination out of 113 countries.Footnote 19 Based on the HHI, in 2017, only Kuwait, Bermuda, and Mexico had a higher geographic concentration of exports than Canada.Footnote 20 Moreover, compared to countries thought to have similar dependence issues, such as Hong Kong SAR with its dependence on China, and New Zealand with its dependence on Australia, Canada’s exports are much more concentrated (Scarffe, 2019b).

The geographic concentration of Canadian exports is not surprising given the high level of exports destined to the United States (Scarffe, 2019a). In fact, the HHI tracks the U.S. share of Canadian exports extremely closely—with a correlation of 0.9997. The HHI increases (a rise in concentration) when the U.S. share of Canadian exports rises, and the HHI decreases, becoming more diverse when the U.S. share declines. In 2018, the U.S. share of Canadian merchandise exports was 75%; while down from 87% in 2002, this is similar to levels seen in the early 90s (the U.S. share of Canadian exports was 75% in 1990).

Data: UN Comtrade

Source: Scarffe, 2019c

Long description

| Rank | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.819 | KWT | Kuwait |

| 2 | 0.665 | BMU | Bermuda |

| 3 | 0.641 | MEX | Mexico |

| 4 | 0.568 | CAN | Canada |

| 5 | 0.563 | CPV | Cape Verde |

| 6 | 0.497 | OMN | Oman |

| 7 | 0.438 | SLB | Solomon Islands |

| 8 | 0.356 | NIC | Nicaragua |

| 9 | 0.343 | NPL | Nepal |

| 10 | 0.313 | ALB | Albania |

| 11 | 0.307 | DOM | Dominican Republic |

| 12 | 0.306 | HKG | Hong Kong SAR, China |

| 13 | 0.284 | ABW | Aruba |

| 14 | 0.249 | SLV | El Salvador |

| 15 | 0.244 | ZMB | Zambia |

| 16 | 0.242 | PLW | Palau |

| 17 | 0.238 | MKD | Macedonia, FYR |

| 18 | 0.237 | JAM | Jamaica |

| 19 | 0.228 | MLI | Mali |

| 20 | 0.224 | SUD | Sudan |

| 21 | 0.220 | BLR | Belarus |

| 22 | 0.203 | MMR | Myanmar |

| 23 | 0.187 | HND | Honduras |

| 24 | 0.182 | BLZ | Belize |

| 25 | 0.175 | MRT | Mauritania |

| 26 | 0.174 | MOZ | Mozambique |

| 27 | 0.172 | WSM | Samoa |

| 28 | 0.151 | KGZ | Kyrgyz Republic |

| 29 | 0.151 | BRN | Brunei |

| 30 | 0.149 | COG | Congo, Rep. |

| 31 | 0.144 | FJI | Fiji |

| 32 | 0.143 | BWA | Botswana |

| 33 | 0.143 | TUN | Tunisia |

| 34 | 0.136 | PRY | Paraguay |

| 35 | 0.135 | NAM | Namibia |

| 36 | 0.133 | AUS | Australia |

| 37 | 0.130 | CZE | Czech Republic |

| 38 | 0.128 | AZE | Azerbaijan |

| 39 | 0.128 | BDI | Burundi |

| 40 | 0.127 | ARM | Armenia |

| 41 | 0.127 | ECU | Ecuador |

| 42 | 0.118 | LUX | Luxembourg |

| 43 | 0.116 | CHL | Chile |

| 44 | 0.117 | IRL | Ireland |

| 45 | 0.111 | ISL | Iceland |

| 46 | 0.110 | PER | Peru |

| 47 | 0.107 | MDG | Madagascar |

| 48 | 0.106 | ISR | Israel |

| 49 | 0.106 | TZA | Tanzania |

| 50 | 0.105 | PRT | Portugal |

| 51 | 0.105 | COL | Colombia |

| 52 | 0.103 | JOR | Jordan |

| 53 | 0.101 | URY | Uruguay |

| 54 | 0.097 | UGA | Uganda |

| 55 | 0.097 | HUN | Hungary |

| 56 | 0.097 | POL | Poland |

| 57 | 0.0967 | NZL | New Zealand |

| 58 | 0.097 | NOR | Norway |

| 59 | 0.096 | KOR | Korea, Rep. |

| 60 | 0.093 | GHA | Ghana |

| 61 | 0.093 | JPN | Japan |

| 62 | 0.092 | TGO | Togo |

| 63 | 0.092 | BOL | Bolivia |

| 64 | 0.091 | MDA | Moldova |

| 65 | 0.090 | PHL | Philippines |

| 66 | 0.089 | LKA | Sri Lanka |

| 67 | 0.084 | SVK | Slovak Republic |

| 68 | 0.084 | MNT | Montenegro |

| 69 | 0.083 | ROM | Romania |

| 70 | 0.081 | DZA | Algeria |

| 71 | 0.081 | NLD | Netherlands |

| 72 | 0.080 | BEL | Belgium |

| 73 | 0.080 | NGA | Nigeria |

| 74 | 0.079 | KAZ | Kazakhstan |

| 75 | 0.078 | BIH | Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| 76 | 0.078 | BRA | Brazil |

| 77 | 0.078 | SVN | Slovenia |

| 78 | 0.077 | MUS | Mauritius |

| 79 | 0.076 | CMR | Cameroon |

| 80 | 0.072 | EST | Estonia |

| 81 | 0.072 | USA | United States |

| 82 | 0.072 | DNK | Denmark |

| 83 | 0.072 | GEO | Georgia |

| 84 | 0.071 | SEN | Senegal |

| 85 | 0.070 | LVA | Latvia |

| 86 | 0.070 | SGP | Singapore |

| 87 | 0.069 | MYS | Malaysia |

| 88 | 0.069 | CYP | Cyprus |

| 89 | 0.068 | HRV | Croatia |

| 90 | 0.066 | CHN | China |

| 91 | 0.066 | CHE | Switzerland |

| 92 | 0.066 | EUN | European Union |

| 93 | 0.065 | IDN | Indonesia |

| 94 | 0.060 | LTU | Lithuania |

| 95 | 0.059 | SER | Serbia, FR(Serbia/Montenegro) |

| 96 | 0.058 | ESP | Spain |

| 97 | 0.056 | RUS | Russian Federation |

| 98 | 0.056 | PAK | Pakistan |

| 99 | 0.056 | FRA | France |

| 100 | 0.055 | FIN | Finland |

| 101 | 0.054 | BGR | Bulgaria |

| 102 | 0.053 | KEN | Kenya |

| 103 | 0.053 | GBR | United Kingdom |

| 104 | 0.051 | SWE | Sweden |

| 105 | 0.050 | ARG | Argentina |

| 106 | 0.048 | IND | India |

| 107 | 0.048 | ITA | Italy |

| 108 | 0.043 | DEU | Germany |

| 109 | 0.040 | EGY | Egypt, Arab Rep. |

| 110 | 0.040 | ZAF | South Africa |

| 111 | 0.040 | GRC | Greece |

| 112 | 0.035 | UKR | Ukraine |

| 113 | 0.035 | TUR | Turkey |

If the United States is excluded from the geographic HHI calculation, we find that Canada scores much better, with an index of 0.07, meaning that outside of the U.S. market, Canadian exports are diversified. Thus, for Canada to improve geographic diversity, Canadian exports need to be less concentrated on the United States. However, the concentration of Canadian exports to the United States is predicated on economic theory. The gravity model of trade tells us that economic size and geographic proximity are the most important determinants of bilateral trade patterns. Having a similar culture (indicated, for example, by language), a common land border, and a free trade agreement further draw Canadian exports to the United States. Also important, there are no other alternatives for Canadian exports nearby as the United States is the only country adjacent to Canada by land. The country that is in a situation closest to Canada, in terms of gravity model determinants, is Mexico—one of the few countries with an HHI higher than Canada. Hence, as with Mexico, it is only natural for Canadian exports to concentrate on the large economy within close proximity to the Canadian border. Thus, diversifying Canada’s exports will require additional and concerted efforts to work against the economic factors that pull Canadian exports toward the United States.

At the HS2 Footnote 21 product level, Canadian exports are found to be diversified, with an HHI score of 0.09 in 2018. This HHI score has changed little over the past 28 years, fluctuating between 0.07 and 0.12 since 1990, but always remaining under the 0.15 benchmark, and thus Canadian exports are considered diversified by product.

That Canadian exports are diversified by product may not have been the ex ante expectation since Canada is known for its energy and auto exports. These sectors are both critical to the Canadian economy, but because Canada’s overall exports are so large, they make up a relatively small share of exports; in 2018, their respective shares of exports were 22% and 14%.Footnote 22 The U.S. impact on Canadian exports is clear as Canada sends approximately 90% of both auto and energy sector exports to the United States. Again, this underlines how the product and geographic dimensions of diversification intersect.

An HHI indicating that Canadian exports are diversified by product does not mean that Canada is immune to industry-specific shocks. The price of Western Canada Select crude oil went from $US86.56/bbl in June 2014 to $US16.30/bbl in February 2016, causing a shallow recession that lasted two quarters and led the Bank of Canada to cut interest rates twice at the beginning of 2015.Footnote 23 Yet, Canada’s export diversity by product meant that the oil price shock only led to a small economic contraction, and Canada’s economy was able to adjust and resume growth despite the price of oil remaining low.

Data: Government of Alberta, Statistics Canada

Long description

| Date of Oil Prices | Oil Price of Western Canada Select per barrel, in US dollars | Quarter and year for GDP growth | GDP growth in % (measured quarter over quarter, seasonally adjusted annual rate) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan-12 | 86.47 | Q1 2012 | 0.19 |

| Feb-12 | 83.04 | Q2 2012 | 1.35 |

| Mar-12 | 75.01 | Q3 2012 | 0.53 |

| Apr-12 | 70.4 | Q4 2012 | 0.82 |

| May-12 | 75.1 | Q1 2013 | 3.61 |

| Jun-12 | 66.37 | Q2 2013 | 2.35 |

| Jul-12 | 64.28 | Q3 2013 | 3.27 |

| Aug-12 | 69.03 | Q4 2013 | 4.28 |

| Sep-12 | 78.17 | Q1 2014 | 0.57 |

| Oct-12 | 79.88 | Q2 2014 | 3.76 |

| Nov-12 | 72.47 | Q3 2014 | 3.88 |

| Dec-12 | 57.87 | Q4 2014 | 2.85 |

| Jan-13 | 62.11 | Q1 2015 | -2.16 |

| Feb-13 | 58.4 | Q2 2015 | -1.07 |

| Mar-13 | 66.72 | Q3 2015 | 1.41 |

| Apr-13 | 68.87 | Q4 2015 | 0.27 |

| May-13 | 80.93 | Q1 2016 | 2.40 |

| Jun-13 | 75.39 | Q2 2016 | -1.81 |

| Jul-13 | 90.5 | Q3 2016 | 4.41 |

| Aug-13 | 90.97 | Q4 2016 | 2.35 |

| Sep-13 | 83.57 | Q1 2017 | 4.09 |

| Oct-13 | 74.21 | Q2 2017 | 4.40 |

| Nov-13 | 62.62 | Q3 2017 | 1.33 |

| Dec-13 | 58.95 | Q4 2017 | 1.70 |

| Jan-14 | 65.69 | ||

| Feb-14 | 81.54 | ||

| Mar-14 | 79.42 | ||

| Apr-14 | 79.56 | ||

| May-14 | 82.72 | ||

| Jun-14 | 86.56 | ||

| Jul-14 | 82.73 | ||

| Aug-14 | 73.89 | ||

| Sep-14 | 74.35 | ||

| Oct-14 | 70.6 | ||

| Nov-14 | 62.87 | ||

| Dec-14 | 43.24 | ||

| Jan-15 | 30.43 | ||

| Feb-15 | 36.52 | ||

| Mar-15 | 34.76 | ||

| Apr-15 | 40.26 | ||

| May-15 | 47.5 | ||

| Jun-15 | 51.29 | ||

| Jul-15 | 43.49 | ||

| Aug-15 | 29.48 | ||

| Sep-15 | 26.5 | ||

| Oct-15 | 32.78 | ||

| Nov-15 | 27.78 | ||

| Dec-15 | 22.51 | ||

| Jan-16 | 17.88 | ||

| Feb-16 | 16.3 | ||

| Mar-16 | 23.46 | ||

| Apr-16 | 27.88 | ||

| May-16 | 32.52 | ||

| Jun-16 | 36.47 | ||

| Jul-16 | 32.8 | ||

| Aug-16 | 30.9 | ||

| Sep-16 | 30.62 | ||

| Oct-16 | 35.83 | ||

| Nov-16 | 31.89 | ||

| Dec-16 | 37.18 | ||

| Jan-17 | 37.19 | ||

| Feb-17 | 39.14 | ||

| Mar-17 | 35.68 | ||

| Apr-17 | 36.84 | ||

| May-17 | 38.84 | ||

| Jun-17 | 35.8 | ||

| Jul-17 | 36.37 | ||

| Aug-17 | 38.5 | ||

| Sep-17 | 39.93 | ||

| Oct-17 | 39.87 | ||

| Nov-17 | 45.52 | ||

| Dec-17 | 44.02 |

Data: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0014-01

Long description

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical | 165.7 | 164.3 | 163.3 | 172.1 | 173.0 | 177.4 | 189.3 | 206.8 | |||||||

| 2000-2017 Growth rate (4.3 %) | 189.3 | 197.4 | 205.8 | 214.5 | 223.7 | 233.2 | 243.1 | 253.5 | 264.3 | ||||||

| 2011-2017 Growth rate(2.2 %) | 189.3 | 193.6 | 197.9 | 202.4 | 206.9 | 211.6 | 216.3 | 221.2 | 226.2 | ||||||

| 2000-2008 Growth rate (6.4 %) | 189.3 | 201.5 | 214.4 | 228.1 | 242.7 | 258.3 | 274.8 | 292.4 | 311.2 | ||||||

| Target | 284 | ||||||||||||||

Canada’s 2025 target

The Canadian government has recognized the need to further diversify Canadian exports. In its Fall Economic Statement (FES) 2018, the government launched an export diversification strategy, with a target of increasing Canada’s overseasFootnote 24 exports by 50% by 2025. As stated in the FES, “The Export Diversification Strategy will invest $1.1 billion over the next six years, starting in 2018-19, to help Canadian businesses access new markets.

The Strategy will focus on three key components: investing in infrastructure to support trade, providing Canadian businesses with resources to execute their export plans, and enhancing trade services for Canadian exporters”.Footnote 25

Data: Statistics Canada Table 36-10-0014-01, Oxford Economics Global Forecast November 2018, Conference Board Forecast March 2018.

Long description

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical | 165.7 | 164.3 | 163.3 | 172.1 | 173.0 | 177.4 | 189.3 | 206.8 | |||||||

| Oxford Economics Forecast | 197.9 | 203.3 | 209.9 | 216.8 | 223.8 | 231.0 | 238.5 | 246.3 | |||||||

| Historical Growth Rate Forecast | 193.6 | 197.9 | 202.4 | 206.9 | 211.6 | 216.3 | 221.2 | 226.2 | |||||||

| Conference Board Forecast | 203.3 | 212.0 | 223.9 | 235.8 | 247.7 | 260.1 | 271.4 | 283.2 | |||||||

| Target | 284 | ||||||||||||||

To attain this target, Canada’s overseas exports of goods and services need to reach $284 billion by 2025, requiring an average annual growth rate of 5.2% from 2017.Footnote 26 Tran (2019a) looked at both historical growth and leading forecasts to analyze the prospect of reaching the target set in the Fall Economic Statement 2018.

As this analysis was undertaken before 2018 data was available, it looks at historical growth up to 2017 and extends this growth from 2017 to 2025. Figure 20 shows three scenarios of extended historical growth using different historical growth periods. Between 2000 and 2017, Canadian overseas goods and services exports grew 4.3% per year. If this growth trend is extended out to 2025, Canadian overseas exports would reach $264 billion, $20 billion short of the $284 billion target. However, in the period prior to the global financial crisis (2000–2008), Canada increased its overseas exports by 6.4% per year; if we apply this growth rate out until 2025, Canadian exports to overseas markets would be $311 billion, $27 billion higher than the target. In more recent years (2011–2017), Canadian exports to overseas markets only grew by 2.2% per year, which, if extended to 2025, would give Canada $226 billion in overseas exports, $58 billion below the target.

For this OCE analysis, independent forecasts of Canadian goods and services exports from two leading economic forecasters, Oxford Economics and the Conference Board of Canada, were also used. Both forecasts expect global economic conditions between 2017 and 2025 to be more supportive of Canadian exports than global economic conditions prevailing between 2011 and 2017. According to Oxford Economics, Canadian overseas exports are expected to reach $246 billion by 2025, growing 3.3% per year from 2017.Footnote 27 This is $38 billion short of the 2025 target of $284 billion (see Figure 5). The Conference Board of Canada’s forecast points to a 5.2% per year growth in Canadian overseas exports, thus reaching $283 billion by 2025, just slightly below the target.

While global economic conditions are forecasted to be more supportive between 2017 and 2025 than in the recent past, risks to the forecast exist. First, the difference between U.S. GDP growth and overseas GDP growth will be a driving factor to overseas export growth. If overseas growth continues to underperform U.S. growth, Canadian businesses will more likely be drawn to the U.S. market, and overseas exports will underperform. Simply put, the better the U.S. economic performance, the harder it is for Canada to diversify exports. Second are the geopolitical risks and the fact that a developed economy like the United States tends to have lower geopolitical risks due to a strong legal and financial system, democratic institutions, and a market-based economy, in addition to strong historical ties with Canada. The opposite can be found in certain emerging overseas markets. Lastly, there are risks of trade disruption, as rising anti-trade sentiments have led to tensions among major economies in the world, many of which are Canada’s main trading partners. It is difficult to predict the outcome of trade tensions. Potential negative impacts could include disruptions to global value chains, declines in income and world demand, and the creation of competing trade blocs, all of which would harm Canadian exports. On the other hand, resolving the issues that led to rising tensions in the first place could create a stronger trade relationship that would be beneficial for global trade.

Chapter 3.1 Key Take-aways:

- There are several dimensions to trade diversification. These include but are not limited to: geographic, product, regional spread of exporters, type of exporter, and ownership.

- Canada has room to diversify, especially in the geographic dimension where currently Canadian exports are considered concentrated.

- The Canadian government has made trade diversification a goal, with the target of increasing overseas exports by 50% by 2025.

Chapter 3.2

What can we do to further

diversify Canadian exports?

At a

glance

Long description

| Road to Diversification |

|---|

| 1. Lower trade barriers through FTAs - FTAs can reduce tariffs, quotas and non-tariff barriers |

| 2. Get in early on fast growth markets - Emerging market and developing economies grew annually by 9.1% between 2000 and 2018, far outpacing advanced economies. |

| 3. Diversify through U.S. - Most exporters move into new markets after exporting to the U.S. first |

| 4. Digital trade - Between 2006 and 2016, exports of ICT enabled services grew 67% |

| 5. Facilitate SMEs - In 2017, SME made up 99.8% of Canadian employer businesses but only 11.7% exported |

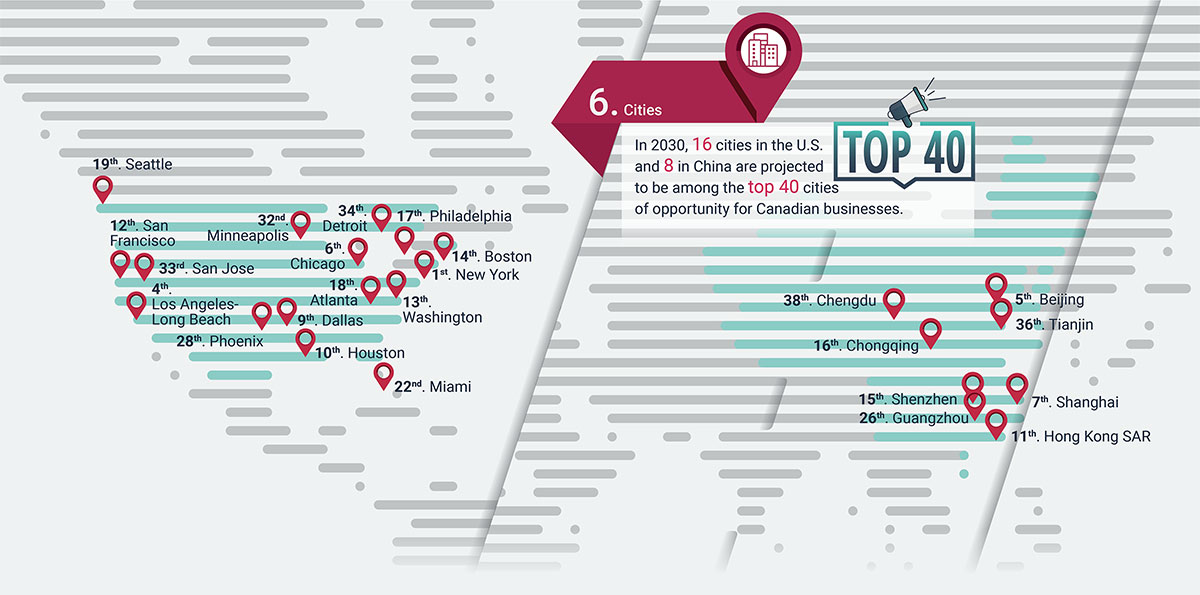

| 6. Cities - In 2030, 16 cities in the U.S. and 8 in China are projected to be among the top 40 cities of opportunity for Canadian businesses |

Long description

| Chinese cities in the top 40 |

|---|

| 5th. Beijing |

| 7th. Shanghai |

| 11th. Hong Kong |

| 15th. Shenzhen |

| 16th. Chongqing |

| 26th. Guangzhou, Guangdong |

| 36th. Tianjin |

| 38th. Chengdu, Sichuan |

| U.S. cities in the top 40 |

|---|

| 1st. New York |

| 4th. Los Angeles - Long Beach |

| 6th. Chicago |

| 9th. Dallas |

| 10th. Houston |

| 12th. San Francisco |

| 13th. Washington |

| 14th. Boston |

| 17th. Philadelphia |

| 18th. Atlanta |

| 19th. Seattle |

| 22nd. Miami |

| 28th. Phoenix |

| 32nd. Minneapolis |

| 33rd. San Jose |

| 34th. Detroit |

Countries don’t trade, firms and people within countries do. What the Canadian government can do is try to foster an environment that allows Canadian firms to engage in global markets and take advantage of the opportunities they present. The Government of Canada can also help reduce trade frictions (costs) by, for example, negotiating tariff reductions and harmonizing standards in trade agreements, providing exporters with market intelligence, or offering export insurance. The government can also help lower barriers faced by Canadian exporters and provide support and tools to aid Canadian firms looking to expand in markets abroad. The following looks at some possible ways in which Canadian exports could be further diversified.

Lowering trade barriers through free trade agreements

According to Global Affairs Canada, “Free Trade Agreements FTAs open markets to Canadian businesses by reducing trade barriers, such as tariffs, quotas or non-tariff barriers. They create more predictable, fair and transparent conditions for businesses operating in foreign countries. Canada’s FTAs cover substantially all trade between parties to the agreement. Many of Canada’s FTAs also go beyond ‘traditional’ trade issues to cover areas such as services, intellectual property and investment.”Footnote 28

With the implementation of the Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and the ratification of the Comprehensive the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), Canada has 14 FTAs with 51 countries. These FTA partners accounted for 62% of world GDP in 2018. By lowering barriers to trade, these FTAs can help diversify Canadian exports and expand overseas trade. Two recent OCE analytical reports looked at the benefits of FTAs to Canadian exporters; the first report analyzed the benefits from CETA, and the second investigated the benefits from the Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement (CKFTA).Footnote 29

CETA entered into force on September 21, 2017. At the time, CETA was by far Canada’s most ambitious trade agreement since NAFTA, both due to the importance of the EU as a trading partner (collectively, the EU is Canada’s second-largest trading partner after the United States) and the scope of the agreement, which set new standards in trade of goods and services, non-tariff barriers, investment, and government procurement, as well as in other areas like labour and the environment.

Boileau (2018) analyzed the performance of Canadian merchandise exports to the EU for the first twelve months CETA was in force.Footnote 30 The analysis found that Canadian exports rose 3.8% (compared to the 12-month period a year earlier), and that if precious stones and metals (HS 71) were excluded, Canadian exports rose 13%. However, there were some sectors where Canadian exports to the EU saw much greater gains, the five largest being aluminum (up 280%), motor vehicles and parts (81%), inorganic chemicals (73%), mineral fuels and oil (63%) and miscellaneous base metals (56%).Footnote 31

The analysis also looked at the impact of the elimination or reduction of tariffs on Canadian merchandise exports to the EU.Footnote 32 The analysis revealed that products that saw the largest declines in tariffs as a result of CETA also showed the largest trade gains. Focusing on the same 12-month period, products exported from Canada to the EU with a greater than 5 percentage point (pp) tariff rate decline were up by 25% compared to products exported without any tariff reduction, which fell 4.3%.

*Export increases were calculated using EU imports data from Eurostat

**Percentage point

Data: Eurostat, Office of the Chief Economist calculations

Long description

| Unaffected (%) | -4.3 |

|---|---|

| Affected (%) | -2.4 |

| 0 to 5 percentage points decline | -6.8 |

| 5 to 10 percentage points decline | 26.8 |

| Greater than 10 percentage points decline | 21.5 |

A closer look at the affected products (those on which tariffs were reduced or eliminated) showed that products subject to a 5 to 10 pp decrease in tariffs saw their exports to the EU increase 27%, while those with a greater than 10 pp tariff reduction saw exports rise 22%. Products with a 0 to 5 pp tariff decline fell by 6.8%. Further details on the products leading the gains in these categories can be found in the 2018 report posted on Global Affairs Canada’s website.

While the benefits from CETA are already evident, the agreement has only been in force since October 2017, and it can often take time for the gains from FTAs to accrue. The CKFTA, which entered into force January 1, 2015, offers a longer period to assess the benefits of an FTA.

Michaelyshyn and Yu (2019) analyzed the effect of the CKFTA on both Canadian exports and imports to/from South Korea over the four years the agreement has been in force (2015 to 2018). The analysis found that total merchandise exports from Canada to South Korea rose from $6.0 billion in 2014, the year prior to the CKFTA entering into force, to $7.5 billion in 2018, an increase of 25%, after overcoming initial declines in 2015 and 2016.Footnote 33 Canadian imports from Korea rose from $7.2 billion to $9.4 billion over the same period, up by 30%.

When looking at the impact of tariff cuts, the report found that exports of all affected products to Korea grew by 36% in the post-CKFTA period (2015 to 2018), compared to a rise of 22% in the pre-CKFTA period (2012 to 2014). Products with the highest tariff cuts had the strongest post-CKFTA growth. This can be observed for products that benefited from tariff reductions of over 10 pp. Exports of these products from Canada to Korea grew by 46% in the post-CKFTA period, compared to 3.4% in the pre-CKFTA period.

Looking at Canadian imports from Korea, the report found that both affected and unaffected products had similar growth in the post-CKFTA era. There was a strong increase in import growth of products that benefited from tariff reductions of 0.1 to 5 pp. Imports of these products grew by 46% in the post-CKFTA period, compared to 24% in the pre-CKFTA period. See Figure 7 for more details.

Table 23: Growth in trade between Canada and Korea by level of tariff reduction

| Tariff Reduction (percentage point) | Between 2012 and 2014 ($ millions) |

Between 2012 and 2014 (%) |

Between 2015 and 2018 ($ millions) |

Between 2015 and 2018 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 to 5 | 160,6 | 22,0 | 608,9 | 100,9 |

| 5.1 to 10 | 194,7 | 26,7 | -54,2 | -5,4 |

| Above 10 | 7,1 | 3,4 | 110,0 | 46,2 |

| All affected products | 362,4 | 21,7 | 664,7 | 35,9 |

| All unaffected products | 392,4 | 11,0 | 1,718,0 | 53,3 |

| All products | 754,8 | 14,4 | 2 382,7 | 47,0 |

Data: Statistics Canada and Ministry of Strategy and Finance Korea

| Tariff Reduction (percentage point) | Between 2012 and 2014 ($ millions) |

Between 2012 and 2014 (%) |

Between 2015 and 2018 ($ millions) |

Between 2015 and 2018 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 to 5 5 | 65,0 | 24,3 | 187,3 | 45,6 |

| 5.1 to 10 | 400,4 | 14,6 | 350,5 | 10,2 |

| Above 10 | 2,7 | 7,0 | 7,5 | 14,8 |

| All affected products | 468,1 | 15,3 | 545,3 | 14,0 |

| All unaffected products | 410,7 | 12,4 | 646,8 | 14,9 |

| All products | 878,8 | 13,8 | 1 192,2 | 14,5 |

* Export increases were calculated using Korean import data from the Ministry of Strategy and Finance Korea

Data: Statistics Canada and Ministry of Strategy and Finance Korea

Looking at Canadian imports from Korea, the report found that both affected and unaffected products had similar growth in the post-CKFTA era. There was a strong increase in import growth of products that benefited from tariff reductions of 0.1 to 5 pp. Imports of these products grew by 46% in the post-CKFTA period, compared to 24% in the pre-CKFTA period.

Both OCE analyses indicate that free trade agreements are effective means of lowering barriers for Canadian exporters to access foreign markets, with Canadian exports gaining in post-FTA periods, especially for products with higher tariff reductions. While Canada already has an extensive array ofFTA partners, entering into an FTA with countries that have not yet signed such agreements with Canada and deepening existing FTAs are other ways Canada may be able to help further diversify Canadian trade.

Global Affairs Canada is actively engaged in promoting CETA, CKFTA and Canada’s other free trade agreements to make sure Canadian exporters are aware of their benefits, and how their products and services would be treated under these agreements. Canadian companies are encouraged to visit Global Affairs Canada’s website to find out how they can benefit from CETA, CKFTA, CPTPP and Canada’s other free trade agreements.

Getting in early in

fast-growing markets

A country’s economic size plays a large role in its demand for imports, and thus growth in a country’s imports is driven by its GDP growth. But not all countries grow at the same rate. GDP dataFootnote 34 indicates that world output expanded at an average annual rate of 5.2% between 2000 and 2018. However, there was a large disparity between growth in advanced economies, which posted an average rate of 3.7% over this period, and emerging market and developing economies,Footnote 35 which grew at a much faster rate of 9.1%. The two largest emerging markets, China and India, experienced real GDP average annual growth of 9.1% and 7.3%, respectively. Conversely, Canada’s main trading partner, the United States, grew at an annual average rate of 1.9% over the same period. One would presume that faster growing markets such as China and India would provide a great opportunity for Canada to further diversify its exports and gain from expanding GDP and demand for imports in these economies. While economic theory suggests that Canadian exports will naturally gravitate to large markets, Scarffe (2019c) investigates whether or not there is a benefit to trading with fast-growing economies; specifically, is there a benefit for Canada to make a strategic effort to increase exports to these economies, and is it better to access these markets early on in their growth.

The study uses a gravity model framework and preliminary results suggest that there are benefits to exporting to fast-growing economies; specifically over a five-year period, the study found that a 1 pp increase in the growth rate of a foreign country's product specific import market caused the level of Canadian exports to increase by 0.11%, and there was an additional gain of 0.16% if Canada was active in this market prior to its growth.Footnote 36 Based on these results, the study concluded that “considering the strong correlation between the growth of import markets and GDP growth, Canada should continue to encourage firms to trade with fast-growing emerging markets”.

Helping Canadian exporting firms engage with and navigate fast-growing emerging markets, particularly at early stages of their growth, appears to be another strategy that could help Canada further diversify its exports.

Diversifying through the United States

Encouraging Canadian exporters to engage in new and fast-growing markets is not a simple proposition. Firm-level research by Yu (2019) reveals particular patterns as to what paths Canadian exporters take to exporting to new markets. First, 70% of existing exporters sell to a single market, usually the United States. Then, only 20% sell to between two and five markets, and 9.3% sell to six or more markets.Footnote 37 These findings corroborate the research by Export Development Canada (EDC) which indicates that most Canadian exporters sell a select few products to only one export market (see Export Development Canada's findings on diversification “Patterns and benefits of Canadian export diversification”).

Each year, roughly 20% of Canadian exporters cease exporting and a somewhat larger number begin to export for the first time. Approximately 80% of new exporters are small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that export to a single market and almost 70% of new exporters choose the United States as their first export destination. Survival rates for these first-time exporters are low with roughly half stopping exporting after their first year. Only 30% of first-time exporters are still exporting four years later, on average. The survival rates are even lower for exporters selling to more distant regions.Footnote 38 However, for exporters that became established, export levels rose rapidly (see Figure 23).

Data: Statistics Canada, Office of the Chief Economist calculations

Long description

| Series 1 | |

|---|---|

| Entry | 151 |

| Year 1 | 567 |

| Year 2 | 804 |

| Year 3 | 840 |

| Year 4 | 1109 |

| Year 5 | 1258 |

| Year 6 | 1414 |

Those exporters that survive begin to diversify into other markets beyond the United States. Each year, 20% of all exporters move into new markets. The diversification strategy of Canadian exporters predominantly takes the form of a series of sequential moves with the same product starting in the U.S. market followed by expansions to either Europe or Asia. This research highlights that the U.S. market is an important first market for most SME exports as well as a proving ground for many that go on to diversify into overseas markets.

What this firm-level research seems to be telling us is that few exporters (20%) move into new markets, and most move to a new market after exporting to the United States first. Although it may seem counterintuitive, a big piece of the puzzle for increasing Canada’s overseas exports may be to encourage and help new Canadian firms to first export to the United States.

Export Development Canada's findings on diversification

Patterns and benefits of

Canadian export diversification

Export Development Canada (EDC) research* finds that most Canadian merchandise exporters (89%) sell to five or fewer markets, typically the United States. At the same time, most companies export only a few products, with 75% of exporters exporting five or fewer products.

However, the pattern for Canadian merchandise export value is quite different; most merchandise exports by value (42%) are generated by a small subset of firms (4%) that export many products (11+) to many export markets (11+).

Table A: Canadian merchandise exporters and exports, by number of markets and products (percentages of totals) Number of exporters

| Number of export products |

Number of export markets 1 to 5 |

Number of export markets 6 to 10 |

Number of export markets 11+ |

Number of export markets Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 5 | 72 % | 2 % | 1 % | 75 % |

| 6 to 10 | 10 % | 2 % | 1 % | 13 % |

| 11+ | 6 % | 2 % | 4 % | 12 % |

| Total | 89 % | 6 % | 6 % | 100 % |

Source: Statistics Canada and EDC Economics

Note: Annual averages using 2010-15 firm-level data.

| Number of export products | Number of export markets 1 to 5 |

Number of export markets 6 to 10 |

Number of export markets 11+ |

Number of export markets Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 5 | 13 % | 1 % | 2 % | 16 % |

| 6 to 10 | 8 % | 2 % | 3 % | 13 % |

| 11+ | 17 % | 11 % | 42 % | 71 % |

| Total | 38 % | 14 % | 47 % | 100 % |

Source: Statistics Canada data with EDC calculations

Note: Annual averages using 2010-15 firm-level data.

EDC research also finds that those exporters able to reach new markets and export more products exhibit superior firm performance.

Along with greater exports, they also have higher output, employ more workers and pay higher wages than firms of similar size and in similar industries that export to fewer markets or export fewer products.

Source: Statistics Canada and EDC Economics

Note: Regression results controlling for year, industry and employment, using 2010-15 annual data.

* Tapp, Stephen and Yan, Beiling 2019 “Patterns and Benefits of Canadian Export Diversification”, Export Development Canada (EDC), Research and Analysis Department, work in progress.

Long description

| New export market | New export product | |

|---|---|---|

| exports | 19.8 | 8.1 |

| output | 7.5 | 4 |

| employment | 6.3 | 3.4 |

| wages | 1 | 0.5 |

Digital trade and diversification

While it is important to look at past and current trends in how Canadian exporters access markets, we must also realize that the way Canadian firms export and reach foreign markets is ever changing and evolving. This may be truer today than ever before. The Internet, digital technologies and the movement of data within an economy and across borders are changing the nature of activities, patterns and actors in the economy at large, with notable implications for international trade in goods and services.

Research by Tran (2019b) has identified two major ways technology and digitization are affecting international trade: 1) digital technologies enable international trade through facilitating transactions and reducing costs; and 2) the Internet is also a delivery mode for international trade.

Digital trade-enabling technologies

Digital technologies enable trade through reductions in time and costs, in addition to being a channel that facilitates transaction processes. From a reduction in time and costs perspective, digital technologies have improved transportation and logistics, effectively shortening distances. Furthermore, new technologies facilitate more efficient route planning and allow exporters to make real-time adjustments en route. They also allow for optimizing storage and distribution networks. Digital technologies also make it easier to cross borders. With Electronic Data Interchange, exporters/importers can file documents electronically at the border, and Electronic Single Window lets exporters/importers submit all their documentation at one place instead of several, reducing time and costs. Moreover, digital technologies provide more and better information for both sellers (exporters) and buyers (importers) as the Internet makes it less costly to search, verify, track and translate information, which can potentially increase trust in cross-border transactions. Finally, advances in fintechFootnote 39 facilitate cross-border payments, making them cheaper and more secure. Along with time and cost reductions, the Internet also facilitates transaction processes by giving consumers the ability to order goods and services globally, either directly from a producer or via a digital platform.

The enabling effect of digital technologies may benefit trade in some goods more than others, potentially changing the composition and altering the product diversification of Canadian trade. The World Trade Organization identifies three types of goods that might benefit more from digital technologies’ enabling effect: time-sensitive, certification-intensive and contract-intensive goods. Examples of time-sensitive goods include intermediate goods in just-in-time inventory systems, perishable foods, and life-saving medical supplies. Cross-border trade in these types of products benefits from routing items more efficiently, predicting arrivals and even integrating artificial intelligence into the complex web of production and distribution.

Products that need certification benefit from reduced information asymmetries and search costs. While the Internet of Things, sensors, and blockchain technology can make the production and certification process more transparent, contract-intensive products can use digital technologies to increase trust (for example, with rating and matching systems), which reduces the need to use intermediaries as trust facilitators. Blockchain-smart contracts also have the potential to further enhance trust and reduce the need for inefficient paperwork.

Even with the enabling promise of the Internet and digital technologies, measurements need to catch up in order to improve our understanding of digital trade. Current measurements are either plagued with missing data, misallocated data, or are unable to capture certain aspects of digital trade. For example, current measurements capture all goods that cross a border, but are unable to identify whether or not these goods were digitally ordered. A similar problem exists for services, in addition to the fact that some services data are currently missing from the picture. For example, an individual Canadian delivering language translation services to foreigners over the Internet might not be included in current services trade statistics since these statistics focus on transactions by businesses.

The Internet as trade-enabler

The Internet is increasingly being used as a cross-border delivery method for digital goods and services. Due to the data limitations mentioned above, there is not a clear and comprehensive picture of digitally-delivered products trade, but some illustrative data show how information and communication technology (ICT) can enable greater trade in services.

Données : Statistique Canada.

Long description

| ICT services | 37.3 |

| Not potentially ICT-enabled services | 30.2 |

| Potentially ICT-enabled services | 67.4 |

| Total merchandise | 17.4 |

Rostami (2018) identifies three types of services exports: ICT services, potentially ICT-enabled services, and not potentially ICT-enabled services.Footnote 40 The first category includes telecommunication services, computer services and charges for the use of intellectual property related to computer software. The second includes services that could potentially be delivered remotely over an ICT network (examples include insurance, financial services, information services, management services, advertising and related services, and research and development, to name a few). The third category includes services that are not likely to be exported over the Internet (e.g. maintenance/repair services, postal/courier services, construction, non-financial commissions, and equipment rental).

The report illustrates the impact of digitalization on Canadian exports. Between 2006 and 2016, Canadian exports of potentially ICT-enabled services grew 67%, compared to 37% for ICT services exports, 30% for not potentially ICT-enabled services exports, and 17% for total merchandise exports.

Digital technologies and the Internet are both enabling international trade, and many services (and even some goods) are delivered across borders through the Internet. This, in turn, is lowering the effect of distance on trade, and in some cases making it easier for exporters to reach distant markets. Accordingly, it is reasonable to look at digital trade as a useful tool for diversification and increasing overseas exports. Encouraging Canadian exporters to adopt digital technologies and ensuring that all Canadians have access to new and emerging technologies may be another path to diversification. Some early evidence shows that Canadian exporters are more likely to adopt technologies than non-exporters (although the impact of size on technology adoption and exporting status requires further analysis),Footnote 41 and according to Bédard-Maltais (2018), digitally advanced companies are 70% more likely to export.

SMEs and export

diversification

A recent study by Sekkel (2019) looked at the participation of (SMEs) in international trade. Using the Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises as the main source of data, the report found that despite their great importance to the domestic market, SMEs in Canada have little participation in exporting.

Figure 25: Canadian SME Exporters, 2017

Data: Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises 2017

Long description

| 2017 | |

|---|---|

| Non-Exporters | 88.3 |

| Exporters | 11.7 |

Data: Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises 2017

Note: Due to rounding, the total does not add up to 100%

Long description

| 2017 | |

|---|---|

| Non-Exporters | 95.8 |

| Exporters | 4.3 |

Note: Due to rounding, the total does not add up to 100%

SMEs comprise the majority of Canadian companies and make a substantial contribution to the economy. In 2017, there were about 1.2 million SMEs in Canada, representing more than 99% of all employer businesses.Footnote 42 SMEs were responsible for 89% of all private sector jobs in 2017, and they accounted for about 50% of GDP between 2012 and 2014. The importance of SMEs to the overall economy is not unique to Canada. Globally, SMEs represent 95% of all firms, and they account for approximately 50% of GDP and around 60% of employment (World Trade Organization, 2016).

However, significant participation of SMEs in the overall economy is not reflected in exporting. In 2017, only 12% of SMEs, or 85,631 enterprises, exported goods or services outside of Canada.Footnote 43 This relatively low participation of SMEs in international trade is also observed in other OECD economies, where SMEs’ participation ranges between 10% and 25% (OECD, 2018).Footnote 44 Not only is the proportion of exporting SMEs low, but so too is their export intensity.Footnote 45 An average of 4% of the sales of SMEs resulted from exports of goods and services.

This study also identifies various challenges and barriers associated with international activities that smaller and less productive firms are less likely to overcome, relative to large firms. While trade agreements can be mostly effective in reducing tariffs and costs associated with non-tariff barriers, fixed costs such as advertisement and product distribution networks affect smaller firms disproportionately (OECD, 2018).

The international trade literature shows that even though larger and more productive firms have a higher likelihood of exporting (Bernard et al., 2007), there is also evidence of positive spillovers from participating in global markets, where exporters can enhance their productivity and innovation through learning-by-doing. While there is a great deal of heterogeneity among SMEs and opportunities to engage in global markets may not be perceived equally across sectors, the internationalization of SMEs as a policy objective can generate great benefits to the economy.

Encouraging SMEs to export could also help Canada realize its 2025 goal of increasing overseas exports by 50%. Although we have seen from Yu (2019) that most new exporters will first begin exporting to the United States, and many will not survive after one year of exporting, some will succeed and grow and reach out to further markets abroad. The vast number of SMEs in the Canadian economy represents an untapped source of exporters; while some, by their nature, can only focus on domestic markets (for example, restaurants and hair salons), others may be successful exporters waiting for the right opportunity. Government programs that help and support these SMEs could be a further means to diversify Canadian exports, not just along the geographic and product dimensions, but also in spreading the gains of exporting across Canada and among all Canadians.

Cities not countries

As for the geographic dimension of export diversification, the analysis so far has focused on the country level as the destination market of Canadian exports, as this is the common reference for geographic diversification and also the usual basis for tracking international trade statistics.Footnote 46 Yet, Vesselovsky (2019) points out that between now and 2030, cities will be the driving engines of growth and innovation.

To support Canada’s diversification strategy, the study assessed the future location of economic opportunities for Canadian businesses at the city level worldwide. The analysis takes into consideration the future economic growth of some 780 cities and Canada’s current economic ties with them.

The study found that in 2030, the top 40 global cities from a Canadian perspective will be dominated by the influence of the United States and China, which are projected to account for 40% and 20% of these cities, respectively. Regionally, Asia and Oceania are projected to account for 45% of the top 40 cities, leaving only 15% outside the U.S. or the Asia and Oceania regions. Among the top 100 global cities, the number of cities from the United States and China is projected to be approximately equal and account for just over half of the total. Regionally, Asia and Oceania are expected to account for almost half of the top 100 cities. Figure 11 presents the projected top 40 cities of importance to Canada in 2030.

Three key take-aways can be gleaned from this city-level analysis for Canada’s export diversification strategy. First, even in 2030, the United States remains important for Canada, with sixteen of the top 40 cities located there. Second, emerging markets are well represented in the top 40 cities; China in particular will have large fast-growing cities that will be important markets for Canadian goods and services. The third take-away is that diversification is not just about emerging markets. Canada can also diversify by further expanding its exports to some developed overseas markets: the United Kingdom, Japan, France and Australia all have major cities predicted to be of importance to Canada in the future.

Chapter 3.2 Key Take-aways:

Les solutions possibles pour accroître la diversification des exportations canadiennes englobent les suivantes :

- Lowering trade barriers through free trade agreements;

- Accessing fast growing markets early on;

- Diversifying through the United States;

- Encouraging Canadian exporters to adopt digital technologies;

- Facilitating SMEs in exporting; and

- Focus on cities as drivers of economic growth.

Figure 26: Top 40 cities in 2030 for Canada

Long description

| U.S. cities in the top 40 |

|---|

| 1st. New York |

| 4th. Los Angeles - Long Beach |

| 6th. Chicago |

| 9th. Dallas |

| 10th. Houston |

| 12th. San Francisco |

| 13th. Washington |

| 14th. Boston |

| 17th. Philadelphia |

| 18th. Atlanta |

| 19th. Seattle |

| 22nd. Miami |

| 28th. Phoenix |

| 32nd. Minneapolis |

| 33rd. San Jose |

| 34th. Detroit |

Long description

| Chinese cities in the top 40 |

|---|

| 5th. Beijing |

| 7th. Shanghai |

| 11th. Hong Kong |

| 15th. Shenzhen |

| 16th. Chongqing |

| 26th. Guangzhou, Guangdong |

| 36th. Tianjin |

| 38th. Chengdu, Sichuan |

Chapter 3.3

New dimensions of export diversification

At a

glance

Long description

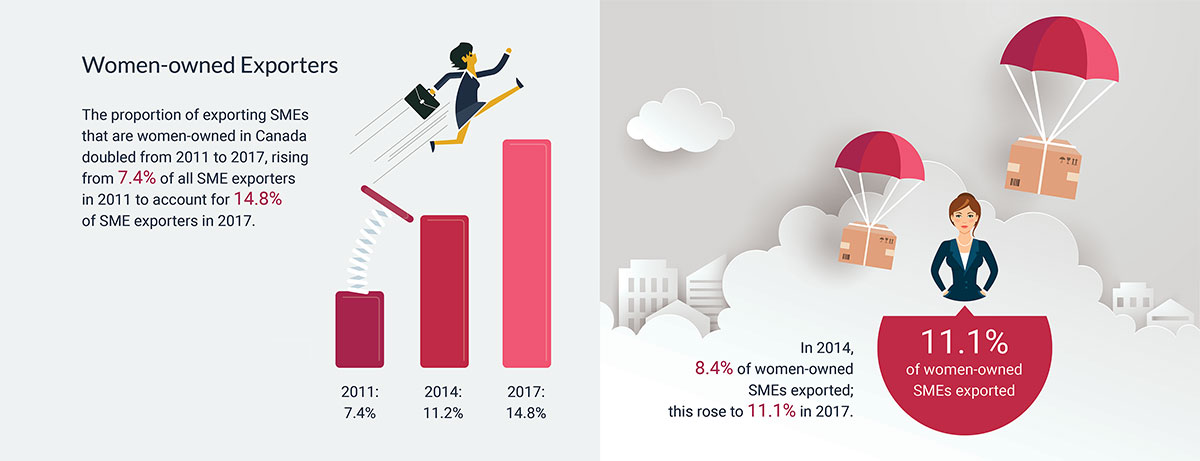

Women-owned Exporters: The proportion of exporting SMEs that are women-owned in Canada doubled from 2011 to 2017, rising from 7.4% of all SME exporters in 2011 to account for 14.8% of SME exporters in 2017.

In 2014, 8.4% of women-owned SMEs exported; this rose to 11.1% in 2017.

| Year | 2011 | 2014 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of exporting SMEs that are women owned | 7.4% | 11.2% | 14.8% |

Long description

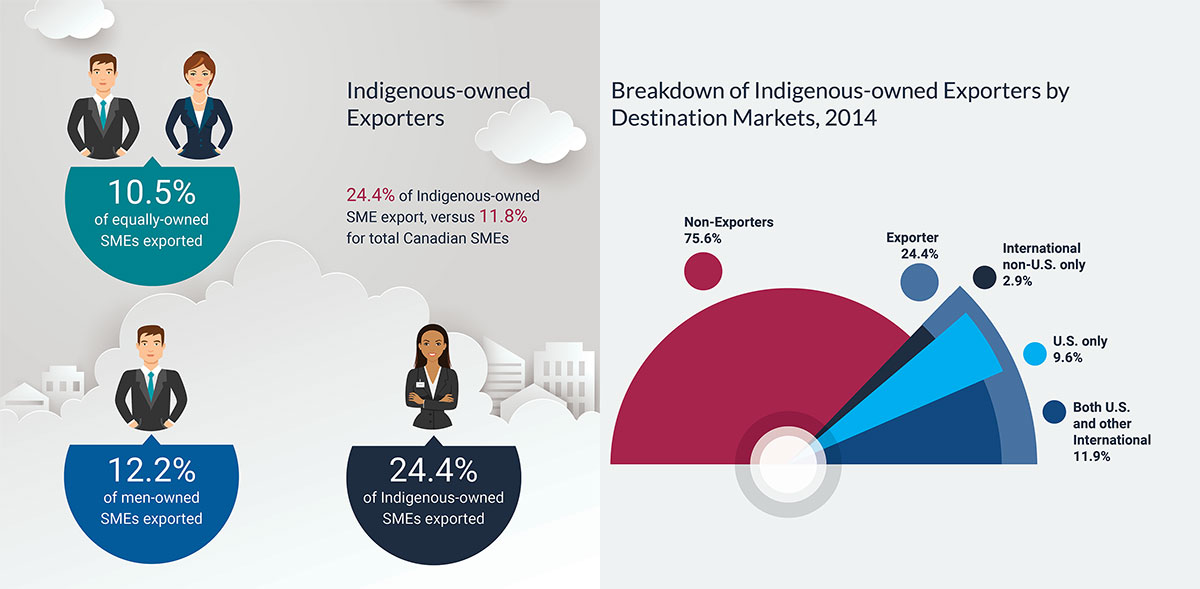

In 2017, the proportion of Men-owned SMEs that exported was 12.2%

In 2017, the proportion of Equally-owned SMEs that exported was 10.5%

In 2014, the Proportion of all Canadian SMEs that exported was 11.8%

In 2014, the Proportion of Indigenous-owned SMEs that exported24.4%

| Breakdown of Indigenous-owned Exporters by Destination Markets, 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Non-Exporters | 75.6% |

| Exporters | 24.4% |

| International non-U.S. only | 2.9% |

| U.S. only | 9.6% |

| Both U.S. and other international | 11.9% |

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, geographic and product diversification are not the only dimensions of diversification. Diversification in ownership of exporting firms is another one. While geographic and product diversification hedge against risk and encourages access to fast-growing markets, ownership diversification has the benefit of spreading the gains of exporting throughout Canada, to all Canadians. Two OCE studies look at exporter ownership. The first examines women-owned small and medium exporters, while the second, a joint research project with the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business (CCAB), looks at Indigenous-owned exporters.

Women-owned exporters

Bélanger Baur (2019a) analyzed the characteristics and internationalization performance of Canadian exporting SMEs based on majority-gender ownership of the firm using data obtained from Statistics Canada’s Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises, 2017. The proportion of exporting SMEs that are women-owned in Canada doubled from 2011 to 2017, rising from 7.4% of all SME exporters in 2011 to 15% in 2017.

The study also indicated that, from 2014 to 2015, and without gaining a larger proportion of all SMEs in the domestic Canadian economy, women-owned SMEs increased their propensity to export such that they are no longer underrepresented among exporter SMEs. In 2014, 8.4% of women-owned SMEs exported; this proportion rose to 11% in 2017. In comparison, 12% of men-owned SMEs exported and 11% of equally-owned (by both men and women) SMEs participated in exporting in 2017.

Note: The export propensity is the percentage of businesses that export. Data: Statistics Canada, Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises, 2011, 2014, 2017.

Long description

| Years | Women-owned SMEs | Equally owned SMEs | Men-owned SMEs | All SMEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 5 | 10 | 11.8 | 10.4 |

| 2014 | 8.4 | 11 | 12.8 | 11.8 |

| 2017 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 11.7 |

The study also looked at the barriers faced by SME exporters when trying to sell goods and services abroad. Although the Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises did not include gender-specific obstacles to exporting, the study found that gender-specific patterns were noticeable. Some 11% of women-owned SMEs reported domestic administrative obstacles as an important barrier to exporting at a greater rate, compared with 10% of men-owned SMEs and 7.6% of equally-owned SMEs. As such, there may be a number of domestic policies that could address barriers to exporting for women-owned SMEs. Additionally, men-owned SMEs report at a lesser rate foreign administrative obstacles to exporting as an important impediment to exports than both women-owned and equally-owned SMEs.

These administrative barriers outside of Canada may take a number of forms, including logistical issues and border obstacles, which women-owned SMEs reported to be important impediments to exporting, at a rate significantly higher than both their counterpart SMEs. The study suggested that federal programs designed to support the internationalization of women-owned SMEs could address the border export requirements of businesses as well as provide additional support with logistical issues.

Interestingly, coming back to the geographic diversification of exports, the study found that a significantly higher proportion of women-owned SMEs export to Europe (including the United Kingdom), India, and the rest of the world (not otherwise mentioned)Footnote 47 compared to men-owned SMEs and equally-owned SMEs. Thus, women-owned SMEs further contribute to the diversification agenda of the Government of Canada.Footnote 48

Indigenous-owned exporters

A joint study by the Office of the Chief Economist at Global Affairs Canada and the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business (Bélanger Baur, 2019b) took a closer look at Indigenous-owned SMEs and their propensity to export.

The study capitalized on data produced by the CCAB using their organization’s register of 10,000 Indigenous-owned businesses, creating a sample of 1,101 Indigenous entrepreneurs, including nearly 650 Indigenous-owned SMEs. Using this unique data set, the author found that a high percentage of Indigenous-owned SMEs sell products and services internationally (24%), compared to Canadian non-Indigenous-owned SMEs (12%) and SMEs in other developed economies.

Footnote 49 The author further writes “Indigenous SMEs, based on these results, demonstrate a strong ability to access broader markets compared to non-Indigenous Canadian SMEs. Given that, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia, Indigenous communities are generally no larger than 1,000 individuals, we suspect Indigenous business strategies may include reaching non-local markets at an early stage, and that the additional cost to sell throughout a province and nationally is relatively small compared to selling to other nearby communities and cities. As such, Indigenous-owned SMEs, notably those owned by First Nations, once operating, would benefit from productivity gains through economies of scale and product specialization as they are forced to become more efficient and overcome challenges related to distance, logistics and connectivity at an early stage.”

Figure 28: Export activities of Indigenous-owned businesses, 2014

Data: Office of the Chief Economist calculations using data obtained from the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business.

Long description

| Non-Exporters | Exporters |

|---|---|

| 75,6% | 24,4 % |

Data: Office of the Chief Economist calculations using data obtained from the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business.

Long description

| U.S. only | International non-U.S. only | Both U.S. and other International |

|---|---|---|

| 9,6 % | 2,9 % | 11,9 % |

The author also looked at the destinations served by Indigenous-owned exporters and found that the most popular destination market of Indigenous-owned exporters, similar to non-Indigenous-owned Canadian exporters, was the United States, with 22% of Indigenous-owned SMEs selling goods or services to our neighbour. Nearly half sell exclusively to the United States, and the other 55% sell to both the United States and other international markets. A small proportion of Indigenous-owned SMEs (2.9%) sell internationally without also exporting to the United States.

More details on the characteristics of Indigenous-owned SMEs can be found in the joint study, including what types of industries Indigenous-owned SMEs are involved in, how these SMEs differ by Canadian region and by Indigenous identity (First Nations, Métis, Inuit). The study also identified obstacles to growth for Indigenous-owned SMEs, notably access to financing and connectivity issues, and how these businesses use social media. This study is the first of its kind to support the development and expansion of Indigenous-owned SMEs into the global trading system. While it indicates Indigenous-owned firms already have a high propensity to export, it also shows that their exports are focused on the United States. Like overall Canadian exports, Indigenous exports could gain from geographic diversification, and in turn having a robust Indigenous export community throughout Canada would help diversify the benefits of trade across the country and to all Canadians.

Chapter 3.3 Key Take-aways:

- Diversification in ownership of exporting firms is another dimension of trade diversification.

- While geographic and product diversification hedges against risk and encourages access to fast growing markets, ownership diversification has the benefit of spreading the gains of exporting throughout Canada, to all Canadians.

- The proportion of women-owned exporting SMEs in Canada doubled from 2011 to 2017, rising from 7.4% of all SME exporters in 2011 to account for 15% of SME exporters in 2017.

- A high percentage of Indigenous SMEs export goods and services (24.4%), compared to Canadian non-Indigenous SMEs (12%).

Conclusion

This chapter has looked at various dimensions of trade diversification, including geographic and product diversification as well as less traditional forms of diversification such as exporter ownership. These dimensions of diversification were shown to be important in hedging risk, allowing access to faster growing markets and helping better distribute the gains of trade.

While Canadian exports were found to be diversified by product, they are concentrated by geographic market. This is the impetus behind Canada’s goal of increasing overseas exports by 50% by 2025.

As for reaching the 2025 goal, chapter looked at various avenues to greater geographic diversity of Canadian exports. These included using free trade agreements to give Canadian exporters better access to foreign markets; accessing fast-growing markets early; using the U.S. market as a stepping stone to overseas markets; leveraging digital technologies; increasing SME participation in international trade; and focusing on cities’ future growth to identify new export opportunities. All of these areas appear promising for boosting Canadian export diversity and should be considered further in the Government of Canada’s trade diversification strategy.

Finally, the chapter investigated a new dimension of trade diversification, that of exporter ownership, summarizing two reports on women-owned exporters and Indigenous-owned exporters, respectively. In both cases, the studies are a good first step in identifying the characteristics of these exporters and what can be done to help women-owned and Indigenous-owned firms in Canada better access global markets. This dimension of trade diversification is particularly important because it is vital in spreading the gains from exporting throughout the Canadian economy, ensuring that they are not concentrated among certain groups of Canadians or regions of Canada, but spread equally across the country.

Bibliography

Bédard-Maltais, Pierre-Olivier. “Digitize Now: How to Make the Digital Shift in Your Business.” Business Development Bank of Canada (2018). https://www.bdc.ca/en/about/sme_research/pages/digitize-now.aspx

Bélanger Baur, Audrey. “Women-owned Small and Medium Enterprise Exporters in Canada.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019a).

———. “Indigenous-owned Exporting Small and Medium Enterprises in Canada.” Global Affairs Canada and the Canadian Council of Aboriginal Business (2019b). https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/assets/pdfs/indigenous_sme-pme_autochtones-eng.pdf

Bernard, Andrew B., Bradford, Jensen, J., Redding, Stephen J. and Peter K. Schott. “Firms in International Trade.” US Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies, No. CES-WP-07-14 (2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1015617

Boileau, David. “Canada’s Merchandise Trade Performance with the EU under CETA.” Global Affairs Canada (2018). https://www.international.gc.ca/economist-economiste/analysis-analyse/merchandise_performance_eu-evolution_marchandise_ue.aspx?lang=eng

European Commission. “Drivers of SME Internationalisation.” European Competitiveness Report (2014), 75‑114. https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d7f09bc3-e57c-42de-ba70-9d06cedfa2d1

Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada; “International Trade and Its Benefits to Canada.” Canada’s State of Trade: Trade and Investment Update 2012 (2012): 111-130. https://www.international.gc.ca/economist-economiste/assets/pdfs/performance/SoT_2012/SoT_2012_Eng.pdf

Michaelyshyn, Katerina, and Emily Yu. “Merchandise Trade Performance since the Canada-Korea Free Trade Agreement Entered into Force in 2015.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Fostering Greater SME Participations in a Globally Integrated Economy.” OECD Discussion Papers (2018). https://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/ministerial/documents/2018-SME-Ministerial-Conference-Plenary-Session-3.pdf

Rostami, Mitra. “Canada’s International Trade in Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) and ICT-enabled Services.” Latest Developments in the Canadian Economic Accounts, Statistics Canada, Cat. No. 13-605-X (2018). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/13-605-X201800154965

Scarffe, Colin. “Benefits from Fast Growing Export Relationships.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019a).

———. “Canada’s Geographic Export Diversity.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019b).

———. “Canada’s Need to Diversify Stronger than Ever.” CanadExport, Global Affairs Canada (2019c). https://www.tradecommissioner.gc.ca/canadexport/0003441.aspx?lang=eng

Sekkel, Julia. “Characteristics of SME Exporters in Canada.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019).

Statistics Canada. “Measuring Canadian Export Diversification.” Latest Developments in the Canadian Economic Accounts, Statistics Canada, Cat. No. 13-605-X (2018b). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/13-605-x/2017001/article/54890-eng.htm

Tran, Tuan. “Growing Canada’s Exports to Overseas Markets by 50 Percent.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019a).

———. “Research on the Digital Economy at Global Affairs Canada.” Presentation to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Workshop on Digital Trade. Santiago, Chile (March 6, 2019b).

Vesselovsky, Mykyta. “Cities of the Future: Urban Opportunities for Canadian Businesses.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019).

World Trade Organization. “World Trade Report 2016: Levelling the Trading Field for SMEs.” World Trade Organization (2016). https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/world_trade_report16_e.pdf

Yu, Emily. “Size and Pattern of Exporter Trade Diversification.” Global Affairs Canada, Office of the Chief Economist, Working paper (2019).