Canada’s performance highlights

Chapter 2.1

Canada’s economic performance

At a

glance

Long description

Canada's Annual GDP Growth 1.9%

Canada's inflation in 2018 2.3%

5.8 % Canada's annual unemployment rate in 2018, the lowest annual unemployment rate on record since 1976

Long description

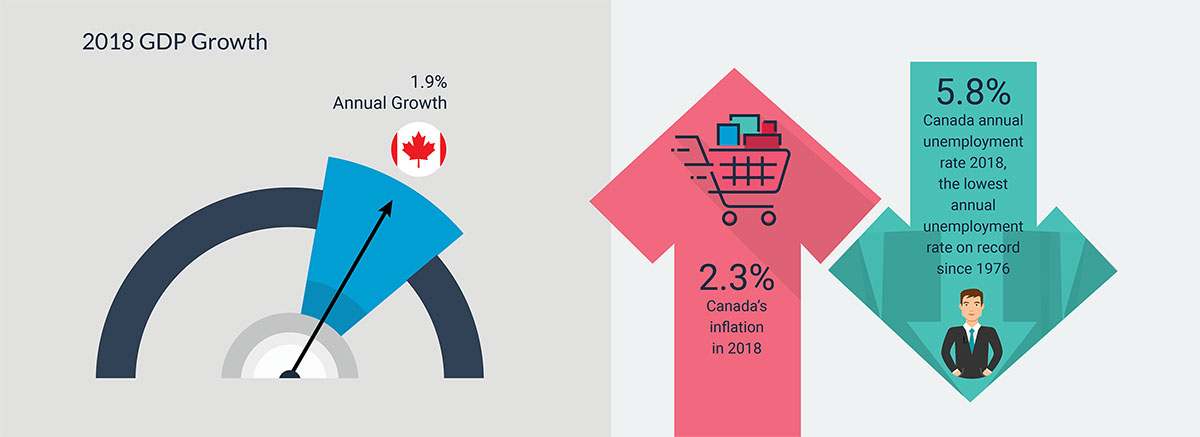

| 2018 GDP Growth, by good sectors in% | |

|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 2.2 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 2.3 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 4.7 |

| Utilities | 0.6 |

| Construction | 0.7 |

| Manufacturing | 2.7 |

| 2018 GDP Growth, by service sectors in% | |

|---|---|

| Services-producing industries | 2.0 |

| Wholesale trade | 1.7 |

| Retail trade | 0.9 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 3.0 |

| Information and cultural industries | -0.2 |

| Finance and insurance | 1.7 |

| Real estate | 1.6 |

| Professional, scientific and technical | 3.3 |

| Educational | 3.0 |

| Health care and social assistance | 2.9 |

| Accommodation and food | 2.2 |

| Public administration | 2.4 |

National overview

After expanding by 3% in 2017, the Canadian economy grew by a more modest 1.9% in 2018. Household consumption was the leading contributor to growth, but that contribution declined to 1.2 percentage points from 2.0 percentage points in 2017. High household debt relative to disposable income played a role in slowing down household consumption. The introduction of tighter mortgage financing guidelines weighed heavily on the housing sector last year as investment in residential structures declined and was a negative contributor to growth. Non-residential business investment contributed positively to growth, but its contribution was low at 0.2 percentage point.

Trade, which had been a drag on growth in 2017, made a marginally positive contribution in 2018. An acceleration in the growth of real exports along with a deceleration in real imports combined to make the turnaround possible.Economic output rose by 1.5% (seasonally adjusted at annual rates) in Q1 2018, then to 2.5% in Q2, before trailing off in the second half of the year (2.1% in Q3 and 0.3% in Q4). With high levels of uncertainty in global affairs (for example, Brexit, NAFTA/ CUSMA negotiations and the global trade tensions), non-residential business investment was lacklustre, contributing negatively to growth over the final three quarters of 2018.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01 and Table 36-10-0128-01; retrieved on 21-06-2019

Long description

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | _ | T1 2018 | T2 2018 | T3 2018 | T4 2018 | T1 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports (Percentage Point) | 0.449 | 0.36 | 0.996 | 1.102 | 3.642 | 0.271 | 0.084 | -1.33 | |

| Business Fixed Investment (Percentage Point) | -0.919 | 0.443 | 0.128 | 0.282 | -0.105 | -1.487 | -1.534 | 0.637 | |

| Personal Consumption (Percentage Point) | 1.246 | 2.041 | 1.155 | 0.72 | 1.059 | 0.762 | 0.545 | 1.96 | |

| Government (Percentage Point) | 0.395 | 0.671 | 0.759 | 0.406 | 0.679 | 0.621 | -0.033 | 0.793 | |

| Inventories (Percentage Point) | -0.016 | 0.821 | -0.265 | 0.028 | -0.646 | -1.157 | 1.273 | 0.729 | |

| Imports (Percentage Point) | -0.059 | -1.413 | -0.927 | -1.384 | -2.068 | 3.205 | 0.224 | -2.536 | |

| GDP Growth in % | 1.107 | 2.979 | 1.879 | 1.48 | 2.533 | 2.11 | 0.251 | 0.401 |

Similar to economic growth, Canadian employment growth moderated in 2018—up by 241,100 jobs compared to 336,500 jobs in 2017. Despite the smaller increase in employment, the unemployment rate fell in 2018, averaging 5.8%, the lowest annual unemployment rate on record since 1976 (and declined to 5.6% in November and December 2018, the lowest monthly rate on record as of the end of 2018).

Concomitantly, average hourly wages grew by 2.9% in 2018, the highest growth since 2012 (2.9%), responding to tighter labour market conditions.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0064-01 and Table 14-10-0327-01; retrieved on 21-06-2019

Long description

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Growth (in thousands of employed) | 256.7 | 217 | 253.1 | 111.1 | 144.4 | 133.3 | 336.5 | 241.1 |

| Unemployment Rate (in %) | 7.5 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 5.8 |

| Average Hourly Wage Growth (in %) | 2.0 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 2.9 |

Inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), grew by 2.3% in 2018, the highest growth since 2011, but within the Bank of Canada’s targeted range of 1–3% for inflation. Leading the growth was the transportation category (4.7%), dominated by the gasoline (13%) and air transportation (15%) sub-categories.

Despite this growth, gasoline and energyFootnote 8 costs were slightly lower than in 2014, a peak year. Excluding energy, the CPI grew by 1.9% in 2018.

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All items | 1.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 |

| Food | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.8 |

| Shelter | 1.6 | 1.7 | 2.0 |

| Household operations | 1.7 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| Clothing and footwear | -0.2 | -0.7 | 0.9 |

| Transportation | 1.1 | 3.9 | 4.7 |

| Gasoline | -6.0 | 11.8 | 12.6 |

| Air transportation | 4.0 | 6.8 | 15.3 |

| Health and personal care | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.3 |

| Recreation and education | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.1 |

| Alcohol and tobacco | 3.2 | 2.7 | 4.2 |

| Special tabulations | |||

| All items excluding food and energy | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| All items excluding energy | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Energy | -3.0 | 5.3 | 6.7 |

| All goods | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.9 |

| All services | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 18-10-0005-01; retrieved on 21-06-2019

On an annual average basis, the Canadian dollar remained relatively steady in 2018 when benchmarked against the US dollar, appreciating by 0.2% compared to 2017.

However, on a monthly average basis, the Canadian dollar has been on a depreciating trend since September 2017.

Source: Bank of Canada; retrieved on 21-06-2019

Long description

| US$ per CAN$ | Nominal Canadian Effective Exchange Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| January 2017 | 0.76 | 118.52 |

| February 2017 | 0.76 | 118.32 |

| March 2017 | 0.75 | 115.36 |

| April 2017 | 0.74 | 114.37 |

| May 2017 | 0.73 | 112.62 |

| June 2017 | 0.75 | 114.47 |

| July 2017 | 0.79 | 119.23 |

| August 2017 | 0.79 | 119.21 |

| September 2017 | 0.81 | 121.96 |

| October 2017 | 0.79 | 119.97 |

| November 2017 | 0.78 | 118.43 |

| December 2017 | 0.78 | 118.3 |

| January 2018 | 0.80 | 120.11 |

| February 2018 | 0.79 | 117.93 |

| March 2018 | 0.77 | 114.71 |

| April 2018 | 0.79 | 116.59 |

| May 2018 | 0.78 | 117.13 |

| June 2018 | 0.76 | 115.82 |

| July 2018 | 0.76 | 115.99 |

| August 2018 | 0.77 | 117.32 |

| September 2018 | 0.77 | 117.47 |

| October 2018 | 0.77 | 118.13 |

| November 2018 | 0.76 | 117.15 |

| December 2017 | 0.74 | 114.95 |

| January 2019 | 0.75 | 115.02 |

| February 2019 | 0.76 | 115.88 |

| March 2019 | 0.75 | 114.59 |

| April 2019 | 0.75 | 114.59 |

| May 2019 | 0.74 | 114.49 |

The price of crude oil is of interest for the Canadian economy, particularly the price differential between West Texas Intermediate (WTI), which is representative of American crude oil pricing, and Western Canadian Select (WCS), which is representative of Canadian oil sands crude oil pricing. WCS oil is heavier than WTI and requires more refining. Because of this, WCS trades at a discount relative to WTI. Typically, the price differential is between US$10 and US$20.

However, in November 2018, the price differential between WCS and WTI widened to US$45.93 per barrel, well beyond the historical average, due mainly to excess supply and the lack of export capacity resulting from transportation bottlenecks. To address these issues and to provide price relief to WCS, the Alberta government put in place mandated crude oil production cuts, and made public its intention to acquire locomotives and rail cars for crude oil transportation.

Source: Government of Alberta, Economics Dashboard; retrieved on 21-06-2019

Long description

| Date | WCS | WTI | Price differential |

|---|---|---|---|

| August 2014 | 73.89 | 96.08 | -22.19 |

| September 2014 | 74.35 | 93.03 | -18.68 |

| October 2014 | 70.6 | 84.34 | -13.74 |

| November 2014 | 62.87 | 75.81 | -12.94 |

| December 2014 | 43.24 | 59.29 | -16.05 |

| January 2015 | 30.43 | 47.22 | -16.79 |

| February 2015 | 36.52 | 50.58 | -14.06 |

| March 2015 | 34.76 | 47.82 | -13.06 |

| April 2015 | 40.26 | 54.45 | -14.19 |

| May 2015 | 47.5 | 59.27 | -11.77 |

| June 2015 | 51.29 | 59.82 | -8.53 |

| July 2015 | 43.49 | 50.9 | -7.41 |

| August 2015 | 29.48 | 42.87 | -13.39 |

| September 2015 | 26.5 | 45.48 | -18.98 |

| October 2015 | 32.78 | 46.22 | -13.44 |

| November 2015 | 27.78 | 42.44 | -14.66 |

| December 2015 | 22.51 | 37.19 | -14.68 |

| January 2016 | 17.88 | 31.68 | -13.8 |

| February 2016 | 16.3 | 30.32 | -14.02 |

| March 2016 | 23.46 | 37.55 | -14.09 |

| April 2016 | 27.88 | 40.75 | -12.87 |

| May 2016 | 32.52 | 46.71 | -14.19 |

| June 2016 | 36.47 | 48.76 | -12.29 |

| July 2016 | 32.8 | 44.65 | -11.85 |

| August 2016 | 30.9 | 44.72 | -13.82 |

| September 2016 | 30.62 | 45.18 | -14.56 |

| October 2016 | 35.83 | 49.78 | -13.95 |

| November 2016 | 31.89 | 45.66 | -13.77 |

| December 2016 | 37.18 | 51.97 | -14.79 |

| January 2017 | 37.19 | 52.5 | -15.31 |

| February 2017 | 39.14 | 53.47 | -14.33 |

| March 2017 | 35.68 | 49.33 | -13.65 |

| April 2017 | 36.84 | 51.06 | -14.22 |

| May 2017 | 38.84 | 48.48 | -9.64 |

| June 2017 | 35.8 | 45.18 | -9.38 |

| July 2017 | 36.37 | 46.63 | -10.26 |

| August 2017 | 38.5 | 48.04 | -9.54 |

| September 2017 | 39.93 | 49.82 | -9.89 |

| October 2017 | 39.87 | 51.58 | -11.71 |

| November 2017 | 45.52 | 56.64 | -11.12 |

| December 2017 | 44.02 | 57.95 | -13.93 |

| January 2018 | 42.53 | 63.55 | -21.02 |

| February 2018 | 37.72 | 62.16 | -24.44 |

| March 2018 | 35.53 | 62.87 | -27.34 |

| April 2018 | 40.47 | 66.33 | -25.86 |

| May 2018 | 53.25 | 69.89 | -16.64 |

| June 2018 | 52.1 | 67.32 | -15.22 |

| July 2018 | 52.83 | 70.74 | -17.91 |

| August 2018 | 48.55 | 67.85 | -19.3 |

| September 2018 | 40.37 | 70.07 | -29.7 |

| October 2018 | 41.15 | 70.76 | -29.61 |

| November 2018 | 11.03 | 56.96 | -45.93 |

| December 2018 | 5.97 | 49.52 | -43.55 |

| January 2019 | 34.3 | 51.38 | -17.08 |

| February 2019 | 45.33 | 54.95 | -9.62 |

| March 2019 | 48.21 | 58.15 | -9.94 |

| April 2019 | 53.25 | 63.86 | -10.61 |

Another issue of interest is the high level of household debt in Canada. While households in the United States have been deleveraging since the 2009 financial crisis, dropping the household debt to GDP ratio to 78% in 2017, Canadian households have not followed suit, and as a result household debt has exceeded 100% of GDP since the second quarter of 2016.

A persistently high and increasing level of household debt can cause constraints to household consumption, an important driver of economic growth. On the other hand, continued strength in the labour market should mitigate some of the negative impact of household debt.

Source: IMF, DataMapper; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Long description

| Date | Canada | United States |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 65 | 85 |

| 2004 | 68 | 89 |

| 2005 | 71 | 92 |

| 2006 | 74 | 96 |

| 2007 | 79 | 99 |

| 2008 | 82 | 96 |

| 2009 | 92 | 97 |

| 2010 | 92 | 92 |

| 2011 | 91 | 87 |

| 2012 | 93 | 84 |

| 2013 | 93 | 82 |

| 2014 | 93 | 80 |

| 2015 | 97 | 78 |

| 2016 | 101 | 78 |

| 2017 | 100 | 78 |

Industry overview

Goods-producing industries grew at 2.2% in 2018, slightly faster than services-producing industries (2.0%). On the goods side, oil and gas extraction was up 7.1% in 2018, causing its share of GDP to increase to 5.5% from 5.3%. Construction grew by a meagre 0.7%, corresponding to slowdowns in housing activity. Within manufacturing, durables grew by 2.5% in 2018, despite a 1.4% decline in motor vehicle and parts manufacturing.

Growth in non-durables was more robust at 2.9%, but negative growth in petroleum and coal product manufacturing mitigated some of the gain. In 2018, growth on the services side was led by professional, scientific and technical services (3.3%), transportation and warehousing services (3.0%), and educational services (3.0%). Growth in real estate services moderated to 1.6% in 2018, after growing by 2.5% the year before. The information and communication technology sector continued to be a bright spot in 2018, growing at 3.5%, though slightly lower than the 4.0% growth in 2017.

| GDP Growth (%) 2016 |

GDP Growth (%) 2017 |

GDP Growth (%) 2018 |

Share of GDP (%) 2016 |

Share of GDP (%) 2017 |

Share of GDP (%) 2018 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | -1.2 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 29.4 | 29.8 | 29.8 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 4.3 | -0.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | -3.4 | 8.8 | 4.7 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 7.8 |

| Oil and gas extraction | 1.5 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.5 |

| Utilities | 1.2 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Construction | -4.4 | 4.4 | 0.7 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.3 |

| Residential construction | 2.9 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| Manufacturing | 0.7 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.5 |

| Durable manufacturing | -0.8 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| Transportation equipment | -0.2 | -2.6 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 2.4 | -2.8 | -1.4 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| Non-durable manufacturing | 2.5 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.9 |

| Petroleum and coal | -1.0 | 6.0 | -3.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Petroleum refineries | -0.9 | 5.1 | -3.2 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Chemicals | 5.1 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Services-producing industries | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 70.5 | 70.2 | 70.1 |

| Wholesale trade | 0.9 | 5.9 | 1.7 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Retail trade | 3.0 | 5.9 | 0.9 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.2 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 2.9 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| Information and cultural industries | 0.9 | 1.3 | -0.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.0 |

| Finance and insurance | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.6 |

| Real estate | 3.0 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 12.7 |

| Professional, scientific and technical | 0.2 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.7 |

| Educational | 1.6 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Health care and social assistance | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 7.0 |

| Accommodation and food | 3.1 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Public administration | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.7 |

| Special industry tabulations | ||||||

| Information and communication technology | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.5 |

| Energy | -1.1 | 7.3 | 2.8 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 9.3 |

| Cannabis | 0.7 | -0.9 | 20.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0434-06; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Overall employment grew by 1.3% in 2018, with goods-producing industries advancing by 1.4% and services-producing industries by 1.3%. On the goods side, utilities employment grew the fastest—at 9.2%—but still only accounts for 0.8% of employment. However, utilities had the highest average hourly wage, at $41, and a low sectoral unemployment rate of 1.7%. Employment in the forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, and oil and gas sector grew by 3.3% in 2018, but overall employment is still below the 2014 peak (373,600), and the sector had the highest unemployment rate and a slower wage growth than average, despite being the second-highest paying sector in terms of average hourly wage.

Employment growth in manufacturing was tepid at 0.2% in 2018, but the unemployment rate (3.6%) and wage growth (3.3%) were solid. On the services side, transportation and warehousing led employment growth at 5.0%, supporting a low unemployment rate of 3.3%; however, wage growth was slightly below average at 2.7%.

| Industry | Employment (‘000s) |

Employment Growth (%) |

Employment Share (%) |

Unemployment Rate (%) | Hourly Wage Average ($) |

Hourly Wage Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods-producing industries | 3,929 | 1.4 | 21.1 | 4.9 | 28.74 | 2.6 |

| Agriculture | 277 | -0.8 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 19.59 | 8.3 |

| Forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas | 341 | 3.3 | 1.8 | 6.8 | 38.46 | 1.3 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 272 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 4.7 | ||

| Utilities | 145 | 9.2 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 41.03 | 2.5 |

| Construction | 1,438 | 2.0 | 7.7 | 6.6 | 29.05 | 1.1 |

| Manufacturing | 1,728 | 0.2 | 9.3 | 3.6 | 26.34 | 3.3 |

| Durables | 1,043 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 3.3 | ||

| Non-durables | 686 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 4.1 | ||

| Services-producing industries | 14,729 | 1.3 | 78.9 | 3.2 | 26.44 | 3.0 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 2,795 | -0.5 | 15.0 | 3.7 | 20.79 | 2.9 |

| Wholesale trade | 656 | -2.5 | 3.5 | 2.6 | ||

| Retail trade | 2,138 | 0.1 | 11.5 | 4.1 | ||

| Transportation and warehousing | 991 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 3.3 | 26.59 | 2.7 |

| Finance, insurance, and real estate | 1,174 | 0.2 | 6.3 | 1.8 | 31.08 | 3.6 |

| Finance and insurance | 829 | -0.3 | 4.4 | 1.8 | ||

| Real estate | 345 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 2.1 | ||

| Professional, scientific and technical | 1,467 | 1.2 | 7.9 | 2.5 | 33.56 | 1.9 |

| Business, building and other support services | 777 | 2.7 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 20.91 | 7.4 |

| Educational | 1,325 | 3.1 | 7.1 | 3.4 | 33.4 | 2.0 |

| Health care and social assistance | 2,407 | 1.0 | 12.9 | 1.6 | 27.51 | 1.3 |

| Information, culture and recreation | 787 | -0.3 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 24.9 | 2.6 |

| Accommodation and food | 1,235 | 2.0 | 6.6 | 5.4 | 15.9 | 5.7 |

| Other services | 803 | 2.8 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 23.42 | 4.6 |

| Public administration | 969 | 0.8 | 5.2 | 2.1 | 36.4 | 3.3 |

| All Industries | 18,658 | 1.3 | 100.0 | 5.8 | 26.92 | 2.9 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0064-01 and Table 14-10-0023-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Provincial and territorial overview

Although Canada has the lowest level of national unemployment since 1976 (5.8% in 2018), disparities in regional employment performance continued to exist in 2018. Notwithstanding strong employment growth in Prince Edward Island (3.1%) and Nova Scotia (1.5%), the Atlantic provinces experienced persistent high rates of unemployment in 2018: Newfoundland and Labrador (14%), Prince Edward Island (9.4%), Nova Scotia (7.5%), and New Brunswick (8.0%). Quebec’s unemployment rate reached a historical low of 5.5%, despite slower employment growth (0.9%). Furthermore, its wage growth was the highest among provinces, at 3.2%. Continued solid employment growth (1.6%) helped lower Ontario’s unemployment rate to 5.6%, the lowest since 1989, and supported wage growth of 2.9%.

As a result of weak employment growth (0.6%), the unemployment rate in Manitoba rose to 6.0% in 2018, from 5.4% in 2017. However, wage growth in the province was solid, at 2.8%. Employment growth in Saskatchewan was the second-weakest among provinces and territories, and the unemployment rate was above the national average. Similarly, Alberta’s unemployment rate was above the national average, however, the province posted the second-fastest employment growth among provinces and territories and had the highest average weekly earnings among the provinces. At 4.7%, British Columbia’s unemployment rate was the lowest among provinces (and at its lowest level since 2008), but the province has the highest inflation rate among all provinces and territories.

| Provinces/Territories | Employment (‘000s) |

Employment Growth (%) |

Unemployment Rate (%) | Weekly Earnings Average ($) |

Weekly Earnings Growth (%) |

Inflation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 18,658 | 1.3 | 5.8 | 1,001 | 2.6 | 2.3 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 225 | 0.5 | 13.8 | 1,038 | 0.3 | 1.6 |

| Prince Edward Island | 76 | 3.1 | 9.4 | 841 | 2.3 | 2.3 |

| Nova Scotia | 456 | 1.5 | 7.5 | 871 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| New Brunswick | 354 | 0.3 | 8.0 | 911 | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| Quebec | 4,262 | 0.9 | 5.5 | 932 | 3.2 | 1.7 |

| Ontario | 7,242 | 1.6 | 5.6 | 1,021 | 2.9 | 2.4 |

| Manitoba | 648 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 937 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| Saskatchewan | 570 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 1,014 | 0.5 | 2.3 |

| Alberta | 2,331 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 1,148 | 1.7 | 2.4 |

| British Columbia | 2,494 | 1.1 | 4.7 | 969 | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Yukon | 21 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 1,118 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

| Northwest Territories | 21 | 0.5 | 7.3 | 1,420 | 1.5 | 2.3 |

| Nunavut | 14 | 0.7 | 14.1 | 1,376 | 3.2 | 3.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0090-01, Table 14-10-0204-01 and Table 18-10-0005-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Looking forward

In conjunction with slowing growth toward the end of 2018, forward-looking economic indicators, such as the Ivey Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) and the Bank of Canada’s Business Outlook Survey (BOS) Indicator, point to a decline in economic sentiment among Canadian businesses. The Ivey PMI, which measures the month-to-month variation in economic sentiment as indicated by a panel of purchasing managers from across Canada, has been trending downward to sit at 50.6 in February 2019, indicating that firms with positive outlooks continue to outnumber firms with negative outlooks, but the gap has been declining.Footnote 9 In recent months, the Ivey PMI has improved slightly to 55.9 in May 2019, but sentiments in the first five months of 2019 are still lower than for the same period last year.

Another indication of softening business sentiment can be seen in the Bank of Canada’s BOS indicator, which has declined since the second half of 2018 from positive levels to a negative one. Results for several BOS survey questions in the spring 2019 edition were below historical averages. The latest edition of theBOS(summer 2019) points to a slight improvement in business sentiment, but weakness tied to Western Canada’s oil industry and global trade tensions continue to dampen outlook.

Source: Ivey Business School; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Long description

| 3-month moving average, seasonally adjusted | |

|---|---|

| 2017-06-01 | 59.3 |

| 2017-07-01 | 58.5 |

| 2017-08-01 | 59.3 |

| 2017-09-01 | 58.6 |

| 2017-10-01 | 59.9 |

| 2017-11-01 | 62.1 |

| 2017-12-01 | 62.4 |

| 2018-01-01 | 59.5 |

| 2018-02-01 | 58.4 |

| 2018-03-01 | 58.2 |

| 2018-04-01 | 63.6 |

| 2018-05-01 | 64.6 |

| 2018-06-01 | 65.7 |

| 2018-07-01 | 62.5 |

| 2018-08-01 | 62.3 |

| 2018-09-01 | 58.0 |

| 2018-10-01 | 58.0 |

| 2018-11-01 | 56.5 |

| 2018-12-01 | 59.6 |

| 2019-01-01 | 57.2 |

| 2019-02-01 | 55.0 |

| 2019-03-01 | 53.2 |

| 2019-04-01 | 53.6 |

| 2019-05-01 | 55.4 |

Soft economic conditions persisted into early 2019, but the Bank of Canada expects activity to pick up later in 2019, resulting in an economy forecasted to grow by 1.2% for the year (April 2019 Monetary Policy Report). The negative effects of low oil prices, housing policy changes, and 2017-18 increases in borrowing rates should fade out later in 2019. The pickup in economic activity is expected to spill over into 2020, supporting Canadian economic growth of 2.1%.

Global trade tensions, for example between the United States and its trading partners, along with tensions between the parties to Brexit are sources of great uncertainty in the economic forecast, as persistent or escalating tensions can reduce foreign demand, disrupt global value chains, lower business confidence and depress commodity prices. On the other hand, if trade tensions are resolved, economic activity could be stronger than expected.

Source: Bank of Canada, Business Outlook Survey, spring 2019; retrieved 28-06-2019

Long description

| Business Outlook Survey Indicator | |

|---|---|

| January 2017 | 0.42 |

| April 2017 | 2.59 |

| July 2017 | 0.71 |

| October 2017 | 2.43 |

| January 2018 | 1.91 |

| April 2018 | 3.13 |

| July 2018 | 2.89 |

| October 2018 | 2.32 |

| January 2019 | -0.65 |

| April 2019 | 0.19 |

Canada’s trade performance

At a

glance

Long description

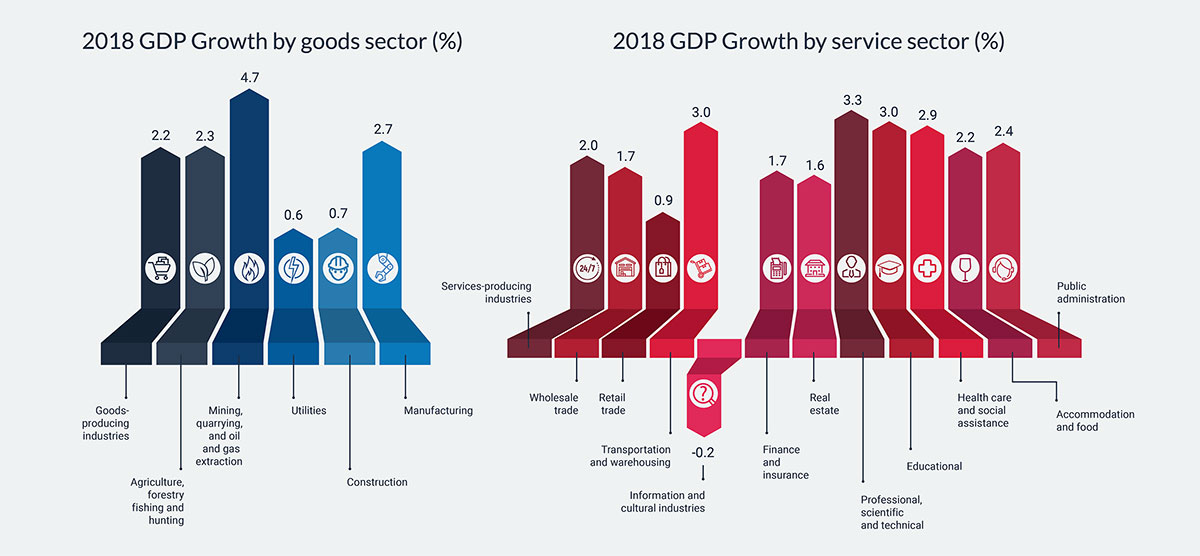

| 2018 Canadian Exports by sectors Value ($B) | 2018 Canadian Exports by sectors Change (%) | 2018 Canadian Imports by sectors Value ($B) | 2018 Canadian Imports by sectors Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods | ||||

| Agri-food and fish | 39.7 | 1.9 | 20.3 | 4.4 |

| Energy | 111.1 | 14.8 | 38.1 | 14.2 |

| Metal ores and minerals | 19.3 | 19.7 | 14.4 | 16.1 |

| Metal and mineral products | 64.6 | 4.8 | 41.5 | 1.4 |

| Chemicals, plastics and rubber | 35.0 | 6.8 | 47.3 | 9.8 |

| Forestry, building and packaging | 47.2 | 7.8 | 26.9 | 5.6 |

| Industrial machinery and equipment | 39.4 | 6.2 | 68.2 | 8.8 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment | 29.4 | 3.5 | 71.3 | 5.4 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 90.5 | -3.0 | 113.8 | 0.2 |

| Aircraft and other transport equipment | 25.8 | 12.7 | 23.8 | 13.8 |

| Consumer goods | 66.6 | 5.7 | 121.4 | 4.9 |

| Services | ||||

| Travel | 28.5 | 8.1 | 43.4 | 5.1 |

| Transportation | 17.9 | 4.9 | 31.6 | 10.0 |

| Commercial | 72.8 | 5.2 | 69.5 | 1.1 |

| Government | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 5.0 |

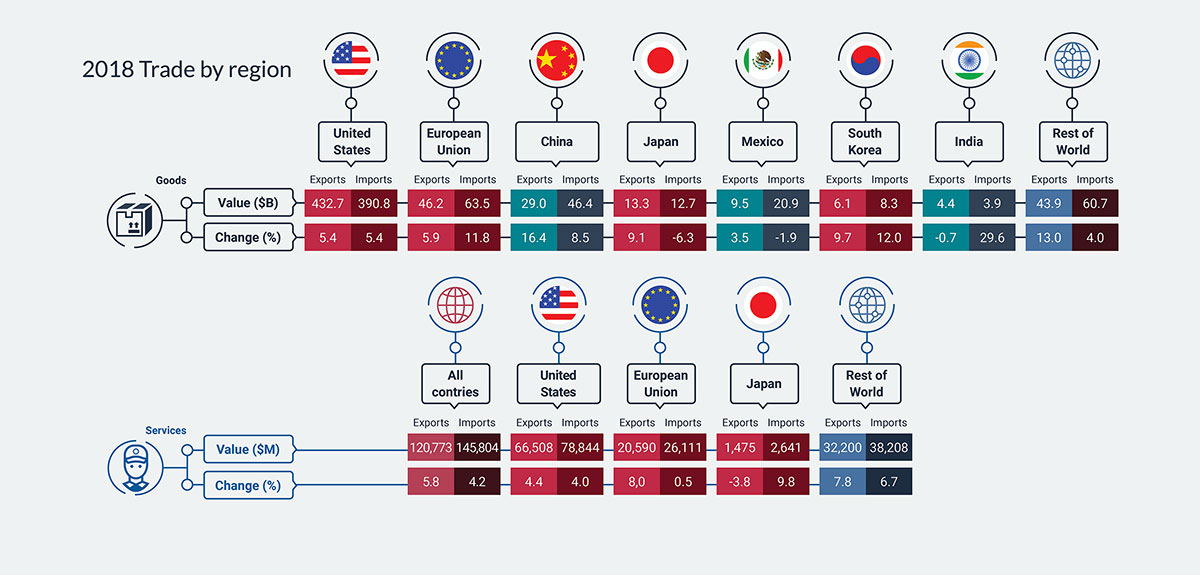

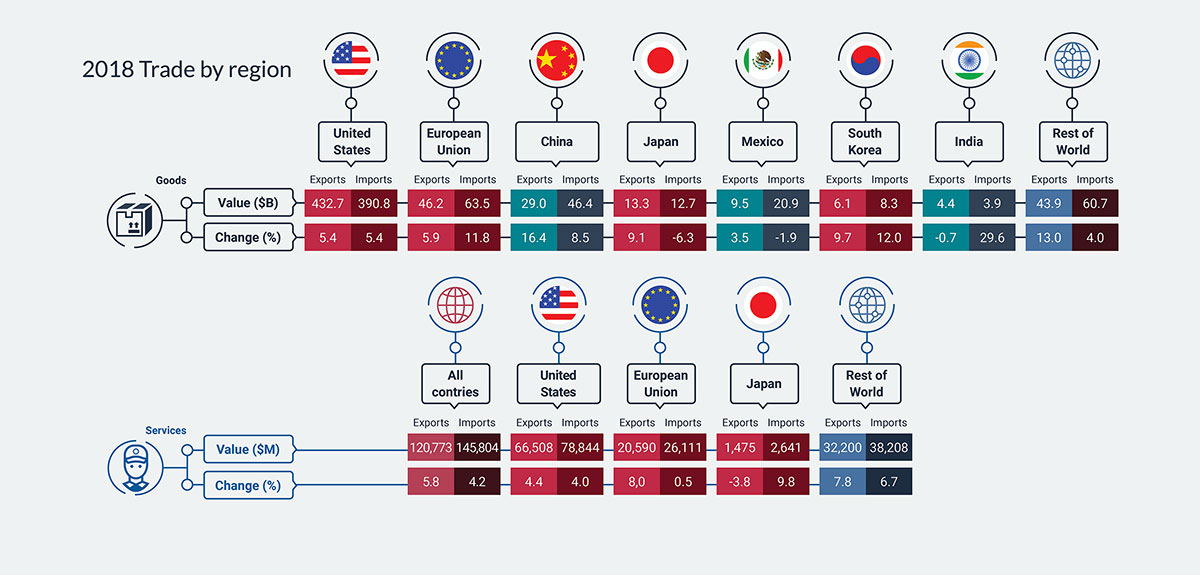

Long description

| 2018 Canadian Exports by regions Value ($B) | 2018 Canadian Exports by regions Change (%) | 2018 Canadian Imports by regions Value ($B) | 2018 Canadian Imports by regions Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods | ||||

| United States | 432.7 | 5.4 | 390.8 | 5.4 |

| European Union | 46.2 | 5.9 | 63.5 | 11.8 |

| China | 29.0 | 16.4 | 46.4 | 8.5 |

| Japan | 13.3 | 9.1 | 12.7 | -6.3 |

| Mexico | 9.5 | 3.5 | 20.9 | -1.9 |

| South Korea | 6.1 | 9.7 | 8.3 | 12.0 |

| India | 4.4 | -0.7 | 3.9 | 29.6 |

| Rest of World | 43.9 | 13.0 | 60.7 | 4.0 |

| Services | ||||

| All countries | 120.8 | 5.8 | 145.8 | 4.2 |

| United States | 66.5 | 4.4 | 78.8 | 4.0 |

| European Union | 20.6 | 8.0 | 26.1 | 0.5 |

| Japan | 1.5 | -3.8 | 2.6 | 9.8 |

| Rest of World | 32.2 | 7.8 | 38.2 | 6.7 |

Long description

| 2018 Canadian Exports by regions Value ($B) | 2018 Canadian Exports by regions Change (%) | 2018 Canadian Imports by regions Value ($B) | 2018 Canadian Imports by regions Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goods | ||||

| United States | 432.7 | 5.4 | 390.8 | 5.4 |

| European Union | 46.2 | 5.9 | 63.5 | 11.8 |

| China | 29.0 | 16.4 | 46.4 | 8.5 |

| Japan | 13.3 | 9.1 | 12.7 | -6.3 |

| Mexico | 9.5 | 3.5 | 20.9 | -1.9 |

| South Korea | 6.1 | 9.7 | 8.3 | 12.0 |

| India | 4.4 | -0.7 | 3.9 | 29.6 |

| Rest of World | 43.9 | 13.0 | 60.7 | 4.0 |

| Services | ||||

| All countries | 120.8 | 5.8 | 145.8 | 4.2 |

| United States | 66.5 | 4.4 | 78.8 | 4.0 |

| European Union | 20.6 | 8.0 | 26.1 | 0.5 |

| Japan | 1.5 | -3.8 | 2.6 | 9.8 |

| Rest of World | 32.2 | 7.8 | 38.2 | 6.7 |

Canada trade overview

Canada’s current account balanceFootnote 10 recorded a deficit of $59 billion in 2018. This was $1.6 billion smaller than in 2017. The lower trade deficit was mainly due to a narrowing of the goods trade deficit by $2.7 billion.

However, these gains were partially offset by the combination of a widening income deficit and the services trade balance moving sideways.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0014-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Long description

| Dates | Current Account Balance ($ Billion) | Goods Balance ($ Billion) | Services Balance ($ Billion) | Income Balance ($ Billion) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | -48 | 5 | -24 | -28 |

| 2015 | -71 | -25 | -25 | -20 |

| 2016 | -65 | -26 | -24 | -15 |

| 2017 | -60 | -25 | -26 | -10 |

| 2018 | -59 | -22 | -25 | -12 |

In 2018, Canada’s exports of goods and services to the world increased 6.2%, or $41 billion, to reach $706 billion, while imports rose 5.4%, or $39 billion, to $753 billion. As both exports and imports expanded, the total value of trade in goods and services reached a record high of $1.5 trillion, or 66% of GDP.

Overall, export prices increased 2.9% while import prices grew 2.4%, and Canada’s terms of tradeFootnote 11 improved for the second consecutive year to 94.5, an improvement of 0.4 percentage point over the previous year.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Long description

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports of Goods and Services (in $ Billion) | 628.9 | 629.1 | 632.4 | 664.8 | 706.0 |

| Imports of Goods and Services (in $ Billion) | 647.6 | 678.3 | 681.2 | 714.4 | 753.0 |

Trade in goods

Canada’s goodsFootnote 12 exports continued to grow in 2018, up 6.5% to $585 billion, with export prices increasing by 2.2% and export volumes expanding by 4.1%.Footnote 13 Concurrently, Canada’s goods imports advanced 5.8% to $607 billion, as both import prices and import volumes increased, up 2.4% and 3.3%, respectively. As a result, total goods trade reached a record high of $1.2 trillion. Moreover, since exports outpaced imports in 2018, Canada’s goods trade deficit narrowed by $2.7 billion to $22 billion.

Exports

Canadian goods exports grew for the second consecutive year in 2018, with export up in all sectors, except motor vehicles and parts. Energy exports growth led the way, advancing $14 billion, or 15%, to reach $111 billion in value, followed by consumer goods (+ $3.6 billion) and forestry, building and packaging products (+ $3.4 billion). Unlike the previous year, the growth of Canadian exports was driven more by an expansion in volumes than in export prices, as volumes were up 4.1% compared to a 2.2% growth in prices. Notable increases in export volumes were registered for metal ores and minerals (+17%), aircraft and other transportation equipment (+12%), and energy products (+8.2%). On the price side, prices of forestry, building and packaging products were up 9.7%.

However, the growth of energy prices slowed from 22% in 2017 to 6.2% in 2018. Crude oil, the main component of this category, experienced large price fluctuations, as its average price rose steadily in the first five months of 2018 and then trended downward slightly until October, before falling sharply in November.Footnote 14 Other sectors that posted strong price increases were metal and mineral products (+5.9%) and chemical, plastic and rubber products (+5.4%). Exports of motor vehicles and parts fell by $2.8 billion, or 3.0%, in 2018, due mainly to a 3.1% decline in export prices.

By destination, goods exports to the United States increased 5.4%, or $22 billion, to $433 billion in 2018. However, exports to non-U.S. destinations grew even faster, up 9.8% (or $14 billion) to $153 billion. As a result, Canada’s goods exports continued to diversify away from the United States. Among Canada’s major non-U.S. trading partners, exports to China recorded the fastest growth (+16%), followed by South Korea (+9.7%) and Japan (+9.1%). Goods exports to the European Union rose modestly (+5.9%), but exports to the Netherlands and Italy posted strong growth, up 51% and 33%, respectively. However, due to falling gold exports, these strong gains were partially offset by declining exports to the United Kingdom (-9.7%).

| Value of Exports, 2018 ($B) |

Change in Value (%) |

Change in Volume (%) |

Change in Price (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 585.3 | 6.5 | 4.1 | 2.2 |

| By product | ||||

| Agri-food and fish | 39.7 | 1.9 | 2.5 | -0.7 |

| Energy | 111.1 | 14.8 | 8.2 | 6.2 |

| Metal ores and minerals | 19.3 | 19.7 | 17.2 | 2.1 |

| Metal and mineral products | 64.6 | 4.8 | -1.0 | 5.9 |

| Chemicals, plastics and rubber | 35.0 | 6.8 | 1.4 | 5.4 |

| Forestry, building and packaging | 47.2 | 7.8 | -1.7 | 9.7 |

| Industrial machinery and equipment | 39.4 | 6.2 | 4.9 | 1.2 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment | 29.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.1 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 90.5 | -3.0 | 0.2 | -3.1 |

| Aircraft and other transport equipment | 25.8 | 12.7 | 11.8 | 0.8 |

| Consumer goods | 66.6 | 5.7 | 4.2 | 1.4 |

| By region/country | ||||

| United States | 432.7 | 5.4 | ||

| European Union | 46.2 | 5.9 | ||

| China | 29.0 | 16.4 | ||

| Japan | 13.3 | 9.1 | ||

| Mexico | 9.5 | 3.5 | ||

| South Korea | 6.1 | 9.7 | ||

| India | 4.4 | -0.7 | ||

| Rest of World | 43.9 | 13.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 36-10-0020-01, 12-10-0126-01 and 36-10-0023-01; retrieved on 24 06 2019

Imports

Canada’s goods imports rose 5.8%, or $33 billion, to $607 billion in 2018. Imports increased in all sectors, led by metal ores and minerals, energy products, and aircraft and other transportation equipment—all of which posted double-digit growth rates. Volumes expanded by 3.3%, led by metal ores and minerals (+13%) and aircraft and other transportation equipment (+12%), while those for metal and mineral products fell by 12%. At the same time, import prices rose 2.4% on the back of higher prices for metal and mineral products (+15%) and energy products (+11%).

Regionally, imports from the United States were up 5.4% to $391 billion in 2018, while imports from non-U.S. sources grew 6.5% to $216 billion. Of Canada’s major non-U.S. trading partners, imports from India recorded the fastest growth at 30% in 2018, followed by imports from South Korea (+12%) and the EU (+12%).

| Value of Imports, 2018 ($B) |

Change in Value (%) |

Change in Volume (%) |

Change in Price (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 607.2 | 5.8 | 3.3 | 2.4 |

| By product | ||||

| Agri-food and fish | 20.3 | 4.4 | 6.5 | -2.0 |

| Energy | 38.1 | 14.2 | 2.9 | 11.0 |

| Metal ores and minerals | 14.4 | 16.1 | 13.1 | 2.6 |

| Metal and mineral products | 41.5 | 1.4 | -11.9 | 15.2 |

| Chemicals, plastics and rubber | 47.3 | 9.8 | 1.6 | 8.1 |

| Forestry, building and packaging | 26.9 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 4.4 |

| Industrial machinery and equipment | 68.2 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 1.3 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment | 71.3 | 5.4 | 7.8 | -2.2 |

| Motor vehicles | 113.8 | 0.2 | 2.3 | -2.1 |

| Aircraft and other transport equipment | 23.8 | 13.8 | 12.4 | 1.2 |

| Consumer goods | 121.4 | 4.9 | 3.8 | 1.1 |

| By region/country | ||||

| United States | 390.8 | 5.4 | ||

| European Union | 63.5 | 11.8 | ||

| China | 46.4 | 8.5 | ||

| Japan | 12.7 | -6.3 | ||

| Mexico | 20.9 | -1.9 | ||

| South Korea | 8.3 | 12.0 | ||

| India | 3.9 | 29.6 | ||

| Rest of World | 60.7 | 4.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 36-10-0020-01, 12-10-0126-01 and 36-10-0023-01; retrieved on 24 06 2019

Trade in services

In 2018, Canadian services exports grew for the ninth consecutive year, up 5.8%, or $6.6 billion, to reach $121 billion, while services imports rose 4.2%, or $5.8 billion, to reach $146 billion. Since services exports slightly outperformed imports, the services trade deficit narrowed by $743 million to $25 billion in 2018. Nevertheless, Canada continued to run a services trade deficit with every broad region and most major trading partners; nearly half of this deficit was with the United States.

By sector

Travel exports accounted for nearly one quarter of services exports in 2018 and were once again the fastest-growing sector, up 8.1% in 2018 to reach $29 billion. Personal travel exports accounted for all the growth in this sector (+9.9%), while business travel declined (-3.6%). Exports of transportation services increased moderately, up 4.9% to $18 billion, with water transportation growing faster than air transportation.

Commercial services exports continued to be the central component of services exports, accounting for over 60% of total services exports. In contrast to last year, commercial services exports rose modestly in 2018, up 5.2%, or $3.6 billion, to reach $73 billion. Gains were led by technical, trade-related and other business services (+$1.2 billion, up 10%), financial services (+$1.0 billion, up 10%) and telecommunications, computer, and information services (+$879 million, up 8.3%), while a $1.2 billion decline in exports of professional and management consulting services partially offset the advance.

On the import side, travel imports rose 5.1% to $43 billion, with imports of both business and personal travel growing at roughly the same rate. Transportation services added $2.9 billion (10%) in 2018, with nearly two thirds of the increase coming from water transportation. Imports of commercial services grew much slower than commercial services exports, only up 1.1% to $69 billion. Imports of financial services fell 7.3% or $895 million, while two small sub-sectors recorded double-digit growth—research and development services (+29%) and personal, cultural, and recreational services (+12%). Other major sub-sectors posted minor changes in 2018.

| 2018 Exports ($M) |

Change (%) |

2018 Imports ($M) |

Change (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Services | 120,773 | 5.8 | 145,804 | 4.2 |

| Travel | 28,514 | 8.1 | 43,449 | 5.1 |

| Business travel | 3,464 | -3.6 | 5,434 | 5.4 |

| Personal travel | 25,052 | 9.9 | 38,016 | 5.1 |

| Transportation | 17,854 | 4.9 | 31,572 | 10.0 |

| Water transport | 3,768 | 9.2 | 14,455 | 14.5 |

| Air transport | 8,388 | 5.9 | 12,720 | 6.5 |

| Land and other transport | 5,700 | 0.7 | 4,396 | 6.0 |

| Commercial services | 72,806 | 5.2 | 69,455 | 1.1 |

| Maintenance and repair services | 2,510 | 26.3 | 986 | 3.6 |

| Construction services | 300 | 8.7 | 294 | 6.9 |

| Insurance services | 2,168 | 10.3 | 5,394 | 9.0 |

| Financial services | 10,839 | 10.3 | 11,410 | -7.3 |

| Telecommunications, computer, and information services | 11,471 | 8.3 | 6,239 | -0.1 |

| Charges for the use of intellectual property | 6,270 | 12.5 | 15,317 | -0.8 |

| Professional and management consulting services | 16,050 | -6.9 | 14,479 | 2.6 |

| Research and development services | 6,759 | 0.3 | 1,612 | 28.5 |

| Technical, trade-related, and other business services | 12,918 | 10.1 | 10,258 | 2.3 |

| Personal, cultural, and recreational services | 3,522 | 7.3 | 3,468 | 11.5 |

| Government services | 1,598 | 0.8 | 1,329 | 5.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0021-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

By region

The overall increase in the value of services exports was led by a $2.8 billion (4.4%) increase in services exports to the United States. Increased commercial services exports accounted for nearly 65% of the growth to the United States, followed by travel services exports. Canadian services imports from the United States also rose by $3.1 billion (4.0%) to reach $79 billion, mainly on higher imports of travel services ($1.6 billion, or 7.5%) and transportation services ($1.2 billion, or 11%). As a result of these balanced movements, the services trade deficit with the United States widened marginally in 2018 to $123 billion.

Services trade with the EU posted a large gain, with Canadian exports rising $1.5 billion, or 8.0%, to reach $21 billion. Most of the gain was in commercial services, which advanced $1.2 billion. At the same time, services imports advanced marginally, up 0.5%, or $131 million, to reach $26 billion.

A decline in services exports and an increase in services imports resulted in a widening of the services trade deficit with Japan to $1.2 billion. The bulk of the movements for both exports and imports occurred in travel services.

In 2018, services exports to the rest of the world (ROW) climbed 7.8% to $32 billion, mainly from an expansion in travel services exports. However, total services exports declined to Australia (-15%), South Korea (-15%), Mexico (-7.1%) and China (-1.8%). On the import side, services imports from ROW rose 6.7% to $38 billion, led by the $1.3 billion increase in imports of transportation services.

| Exports ($M) |

Change (%) |

Imports ($M) |

Change (%) |

Balance ($M) |

Change ($M) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Countries | 120,773 | 5.8 | 145,804 | 4.2 | -25,031 | 742 |

| Travel | 28,515 | 8.1 | 43,450 | 5.1 | -14,934 | 11 |

| Transportation | 17,854 | 4.9 | 31,571 | 9.9 | -13,717 | -2,030 |

| Commercial services | 72,805 | 5.2 | 69,455 | 1.1 | 3,350 | 2,811 |

| Government services | 1,598 | 0.8 | 1,328 | 4.9 | 270 | -50 |

| United States | 66,508 | 4.4 | 78,844 | 4.0 | -12,336 | -279 |

| Travel | 11,096 | 8.1 | 23,318 | 7.5 | -12,222 | -795 |

| Transportation | 8,322 | 2.0 | 11,274 | 11.5 | -2,952 | -997 |

| Commercial services | 46,661 | 3.9 | 43,759 | 0.6 | 2,902 | 1,513 |

| Government services | 428 | 3.4 | 493 | 3.1 | -64 | 0 |

| EU | 20,590 | 8.0 | 26,111 | 0.5 | -5,520 | 1,404 |

| Travel | 3,764 | 2.1 | 6,672 | -3.9 | -2,908 | 347 |

| Transportation | 4,069 | 6.1 | 5,749 | 8.6 | -1,680 | -220 |

| Commercial services | 12,519 | 10.8 | 13,394 | -0.6 | -875 | 1,299 |

| Government services | 239 | 1.3 | 296 | 9.2 | -57 | -21 |

| Japan | 1,475 | -3.8 | 2,641 | 9.8 | -1,166 | -294 |

| Travel | 435 | -16.3 | 605 | 146.9 | -170 | -444 |

| Transportation | 568 | 2.7 | 822 | -6.4 | -254 | 71 |

| Commercial services | 441 | 2.3 | 1,193 | -5.5 | -752 | 79 |

| Government services | 32 | 3.2 | 22 | 0.0 | 10 | 1 |

| Rest of world | 32,200 | 7.8 | 38,208 | 6.7 | -6,009 | -89 |

| Travel | 13,220 | 11.0 | 12,855 | 3.2 | 366 | 903 |

| Transportation | 4,895 | 9.2 | 13,726 | 10.4 | -8,831 | -884 |

| Commercial services | 13,184 | 4.9 | 11,109 | 6.6 | 2,075 | -80 |

| Government services | 899 | -0.7 | 517 | 4.4 | 381 | -30 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0014-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

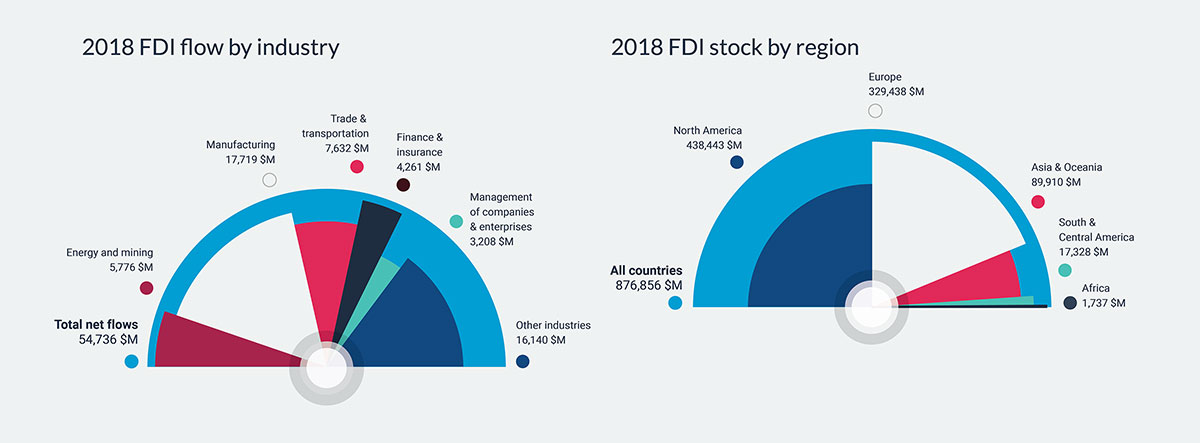

Canada’s foreign direct investment performance

At a

glance

Long description

| 2018 FDI flow by industry ($M) | |

|---|---|

| Total net flows | 54,736 |

| Energy and mining | 5,776 |

| Manufacturing | 17,719 |

| Trade and transportation | 7,632 |

| Finance and insurance | 4,261 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 3,208 |

| Other industries | 16,140 |

| 2018 FDI stock by region ($M) | |

|---|---|

| All countries | 876,856 |

| North America | 438,443 |

| Europe | 329,438 |

| Asia & Oceania | 89,910 |

| South & Central America | 17,328 |

| Africa | 1,737 |

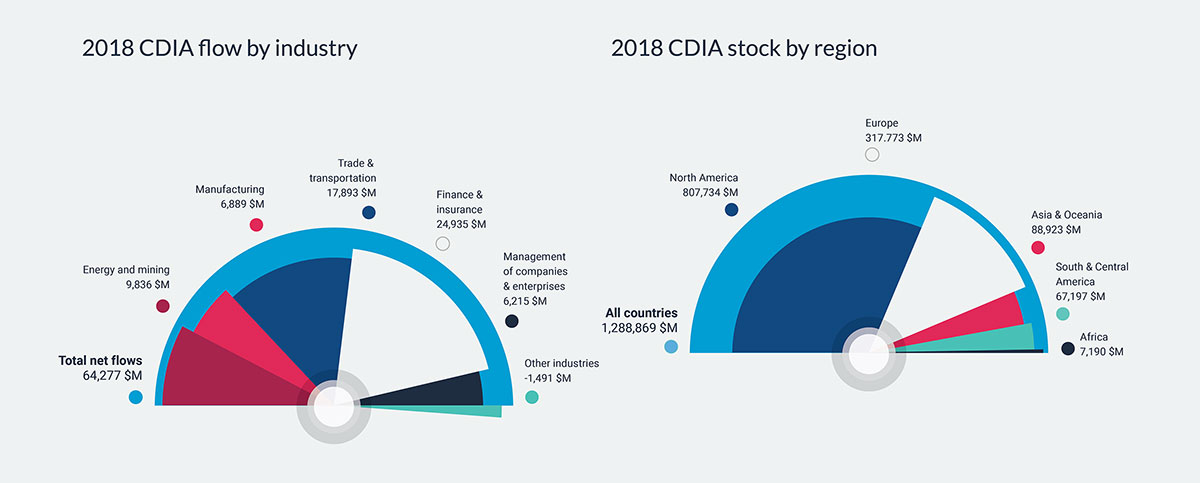

Long description

| 2018 CDIA flow by industry ($M) | |

|---|---|

| Total net flows | 64,277 |

| Energy and mining | 9,836 |

| Manufacturing | 6,889 |

| Trade and transportation | 17,893 |

| Finance and insurance | 24,935 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 6,215 |

| Other industries | -1,491 |

| 2018 CDIA stock by region ($M) | |

|---|---|

| All countries | 1,288,869 |

| North America | 807,734 |

| Europe | 317,773 |

| Asia & Oceania | 88,923 |

| South & Central America | 67,197 |

| Africa | 7,190 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 36-10-0025-01 and 36-10-0008-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Longue description

| CDIA (Flow) ($ Billion) | FDI (Flow) ($ Billion) | CDIA (Stock) ($ Billion) | FDI (Stock) ($ Billion) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 69 | 125 | 515 | 512 |

| 2008 | 85 | 66 | 642 | 551 |

| 2009 | 45 | 26 | 631 | 574 |

| 2010 | 36 | 29 | 637 | 592 |

| 2011 | 52 | 39 | 675 | 603 |

| 2012 | 56 | 43 | 704 | 634 |

| 2013 | 59 | 71 | 778 | 689 |

| 2014 | 67 | 65 | 845 | 745 |

| 2015 | 86 | 56 | 1044 | 783 |

| 2016 | 93 | 48 | 1105 | 811 |

| 2017 | 10 | 32 | 1167 | 835 |

| 2018 | 64 | 55 | 1289 | 877 |

FDI into Canada

In 2018, total flows of FDI into Canada increased by 70% to $55 billion, compared to declines in most other developed economies. This sharp increase was due to a $24 billion (+262%) growth in FDI from non-U.S. sources, mainly from European countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, while flows from the United States declined by 6.8%. The largest total FDI inflows gain came from mergers and acquisitions (M&A) turning positive in 2018, with a net increase of nearly $20 billion. Reinvested earnings also climbed $3.0 billion, while other FDI inflows declined marginally.

By sector, strong flows of investment into Canada’s manufacturing sector (45%) made up for the declines in trade and transportation (-41%) and finance and insurance (-13%). Moreover, investment in other industries nearly doubled. After two major divestures totalling $9.3 billion in 2017, inflows into Canada’s oil sector turned positive in 2018 to reach $5.8 billion.

| Type of FDI Inflows | 2017 ($M) |

2018 ($M) |

Change (%) |

Change ($M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From the world | ||||

| Total net flows | 32,226 | 54,736 | 69.9 | 22,510 |

| Mergers and acquisitions | -4,892 | 15,029 | n/a | 19,921 |

| Reinvested earnings | 23,055 | 26,069 | 13.1 | 3,014 |

| Other flows | 14,062 | 13,638 | -3.0 | -424 |

| From the United States | ||||

| Total net flows | 23,055 | 21,495 | -6.8 | -1,560 |

| Mergers and acquisitions | -4,315 | 4,314 | n/a | 8,629 |

| Reinvested earnings | 14,736 | 13,776 | -6.5 | -960 |

| Other flows | 12,633 | 3,406 | -73.0 | -9,227 |

| From the rest of the world | ||||

| Total net flows | 9,171 | 33,240 | 262.4 | 24,069 |

| Mergers and acquisitions | -576 | 10,715 | n/a | 11,291 |

| Reinvested earnings | 8,317 | 12,294 | 47.8 | 3,977 |

| Other flows | 1,430 | 10,232 | 615.5 | 8,802 |

| Sectors of FDI inflows from the world | ||||

| Energy and mining | -9,333 | 5,776 | n/a | 15,109 |

| Manufacturing | 12,222 | 17,719 | 45.0 | 5,497 |

| Trade and transportation | 12,856 | 7,632 | -40.6 | -5,224 |

| Finance and insurance | 4,891 | 4,261 | -12.9 | -630 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 3,280 | 3,208 | -2.2 | -72 |

| Other industries | 8,312 | 16,140 | 94.2 | 7,828 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 36-10-0025-01 and 36-10-0026-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Foreign investors’ cumulative holdings of direct investment (stock) in Canada expanded by $42 billion, or 5.0%, to reach $877 billion in 2018. Because the stock of FDI grew slightly faster than Canada’s nominal GDP (+3.6%) in 2018, the FDI stock to GDP the ratio of FDI stock to GDP increased from 39% in 2017 to 40% in 2018.

All regions except Africa increased their FDI stock in Canada in 2018. The FDI stock from North America, comprising the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean region, was up 5.2% over the previous year and accounted for exactly half of Canada’s FDI stock. The United States remained Canada’s largest foreign investor by far, with a FDI stock totalling $406 billion in 2018.

The level of inward FDI stock from Europe (4.9%) and Asia and Oceania (4.2%) grew slightly slower. In contrast, the FDI stock from South and Central America recorded the fastest regional expansion in 2018, advancing by 10% to reach $17 billion, almost entirely due to Brazilian investment. However, investment from Africa declined by 12%.

| 2017 ($M) |

2018 ($M) |

Share 2017 (%) |

Share 2018 (%) |

Change (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | 834,757 | 876,856 | 100 | 100 | 5.0 |

| North America | 416,758 | 438,443 | 49.9 | 50.0 | 5.2 |

| United States | 386,869 | 406,051 | 46.3 | 46.3 | 5.0 |

| Bermuda | 15,520 | 16,604 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 7.0 |

| Cayman Islands | 8,002 | 8,912 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 11.4 |

| British Virgin Islands | 3,011 | 2,928 | 0.4 | 0.3 | -2.8 |

| Mexico | 2,696 | 2,730 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Europe | 314,006 | 329,438 | 37.6 | 37.6 | 4.9 |

| Netherlands | 101,861 | 106,706 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 4.8 |

| Luxembourg | 54,627 | 55,828 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 2.2 |

| United Kingdom | 46,988 | 50,353 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 7.2 |

| Switzerland | 44,010 | 46,147 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 4.9 |

| Germany | 16,617 | 17,008 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.4 |

| France | 11,545 | 13,509 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 17.0 |

| Ireland | 7,100 | 8,094 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 14.0 |

| Belgium | 7,669 | 8,015 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 4.5 |

| Asia and Oceania | 86,269 | 89,910 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 4.2 |

| Japan | 28,162 | 28,871 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.5 |

| Hong Kong SAR | 20,075 | 21,802 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 8.6 |

| China | 16,226 | 16,959 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 4.5 |

| Australia | 9,296 | 9,682 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 4.2 |

| United Arab Emirates | 3,156 | 3,441 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 9.0 |

| India | 2,723 | 2,561 | 0.3 | 0.3 | -5.9 |

| South Korea | 2,561 | 2,398 | 0.3 | 0.3 | -6.4 |

| Kuwait | 2,180 | 2,158 | 0.3 | 0.2 | -1.0 |

| South and Central America | 15,749 | 17,328 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 10.0 |

| Brazil | 13,185 | 14,628 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 10.9 |

| Africa | 1,975 | 1,737 | 0.2 | 0.2 | -12.1 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0008-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Compared to a decade ago, the distribution of foreign investors in Canada is slightly more diverse but still dominated by North America and Europe.

North America’s share of FDI stock declined 3.1 percentage points, mainly from the decline in the share of U.S. investors from 52% in 2009 to 46% in 2018, while Europe’s share increased 5.2 percentage points due to increasing investment from the Netherlands and Luxembourg.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0008-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

Long description

| 2009 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|

| North America (in %) | 53.06 | 50.00 |

| South and Central America (in %) | 2.32 | 1.98 |

| Europe (in %) | 32.42 | 37.57 |

| Africa (in %) | 0.42 | 0.20 |

| Asia/Oceania (in %) | 11.78 | 10.25 |

By industry, over 40% of the overall increase in Canada’s inward FDI stock in 2018 came from manufacturing, which added $17 billion (+9.4%) to reach $202 billion in 2018 and reinforce its number one spot with a 23% share of the total FDI stock. Investment in agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting reached historic levels last year, by expanding nearly 26 times over from $182 million in 2017 to $4.7 billion in 2018. Growing FDI in the finance and insurance sector, which was responsible for approximately one quarter of total FDI stock growth in 2017, only contributed 7.5% of FDI stock growth in 2018.

The information and communication technologies (ICT) sector is a specialized R&D-intensive category that is an important driver of productivity growth. Although FDI stock in Canada’s ICT sector expanded 21% to reach $16 billion in 2018, its share of total FDI stock has been trending downward since the early 2000s, from a peak of 9.7% in 2000 to only 1.8% in 2018.

| 2017 ($M) |

2018 ($M) |

Share 2017 (%) |

Share 2018 (%) |

Change (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, all industries | 834,757 | 876,856 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 5.0 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 182 | 4,698 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2,481.3 |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | 173,700 | 175,543 | 20.8 | 20.0 | 1.1 |

| Utilities | 1,510 | 1,356 | 0.2 | 0.2 | -10.2 |

| Construction | 3,566 | 4,300 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 20.6 |

| Manufacturing | 184,915 | 202,352 | 22.2 | 23.1 | 9.4 |

| Wholesale trade | 72,166 | 78,084 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 8.2 |

| Retail trade | 34,253 | 33,979 | 4.1 | 3.9 | -0.8 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 13,702 | 14,219 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 3.8 |

| Information and cultural industries | 3,928 | 5,728 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 45.8 |

| Finance and insurance | 132,096 | 135,250 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 2.4 |

| Real estate, rental and leasing | 12,820 | 15,032 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 17.3 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 18,042 | 19,031 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 5.5 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 172,286 | 174,756 | 20.6 | 19.9 | 1.4 |

| Accommodation and food services | 3,964 | 4,343 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 9.6 |

| All other industries | 7,627 | 8,186 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 7.3 |

| Information and communication technologies (ICT)Footnote 15 | 13,275 | 16,060 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 21.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0009-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

FDI by ultimate investor country

In line with international standards, statistics on source countries of FDI have traditionally been compiled according to the immediate investing country (IIC), which is the last country through which the FDI transited before entering the domestic economy. While this measure is appropriate for evaluating the direct investment flows and corresponding funds exchanged between countries, it does not shed light on the real FDI source country where the ultimate investor originates. Measuring FDI according to the ultimate investor country (UIC) attempts to rectify this problem.

The U.S. share of Canadian FDI by UIC is 51%, larger than its 46% share of FDI by IIC. The United Kingdom, Japan, Switzerland and Brazil round off the rest of the top five UIC rankings, and all these countries rank higher under UIC than under IIC. On the other hand, three of the top five countries under IIC ranking, such as the Netherlands and Luxembourg, play a smaller role in Canadian FDI under UIC ranking. Under UIC, China accounted for 3.3% of Canadian FDI (sixth in the ranking), compared to IIC, where it accounted for 1.9% (ninth in the ranking).

| UIC Rank | Country | Share (%) | IIC Rank | Country | Share (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 51.2 | 1 | United States | 46.3 |

| 2 | United Kingdom | 6.3 | 2 | Netherlands | 12.2 |

| 3 | Japan | 4.7 | 3 | Luxembourg | 6.5 |

| 4 | Switzerland | 3.5 | 4 | United Kingdom | 5.6 |

| 5 | Brazil | 3.3 | 5 | Switzerland | 5.3 |

| 6 | China | 3.3 | 6 | Japan | 3.4 |

| 7 | Germany | 3.2 | 7 | Hong Kong SAR | 2.4 |

| 8 | Luxembourg | 2.7 | 8 | Germany | 2.0 |

| 9 | Netherlands | 2.4 | 9 | China | 1.9 |

| 10 | France | 2.1 | 10 | Bermuda | 1.9 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0433-01 and Table 36-10-0008-01; retrieved on 20-06-2019

Canadian direct investment abroad

In 2018, CDIA presented a completely different picture compared to inflows. CDIA fell 38% to $64 billion, with M&A decreasing by 48%, or $31 billion, and divestment in other flows growing to over $15 billion.

Decreasing CDIA was mostly due to lower investment in the United States, down 60% to $33 billion, mainly caused by the decline in M&A (-77%). In contrast, CDIA flows to the rest of the world surged, up 48%, or $10 billion (almost entirely due to increases in M&A). As a result, the share of CDIA to the United States accounted for only 51% of overall CDIA outflows in 2018, down from nearly 80% the previous year.

By sector, unlike in the previous year, Canadian investors diverted investment from every sector to energy and mining, and manufacturing, adding $13 billion and $10 billion, respectively. Trade and transportation lost the top spot for Canadian investors, as investment flows into this sector were cut by 68% to $18 billion in 2018. As a result, finance and insurance became the new number one sector as CDIA flows declined relatively less, by 12%, to $25 billion.

| 2017 ($M) |

2018 ($M) |

Change (%) |

Change ($M) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To the world | ||||

| Total net flows | 103,591 | 64,277 | -38.0 | -39,314 |

| Mergers and acquisitions | 64,846 | 33,654 | -48.1 | -31,192 |

| Reinvested earnings | 39,312 | 45,980 | 17.0 | 6,668 |

| Other flows | -568 | -15,358 | n/a | -14,790 |

| To the United States | ||||

| Total net flows | 82,492 | 32,944 | -60.1 | -49,548 |

| Mergers and acquisitions | 58,657 | 13,638 | -76.7 | -45,019 |

| Reinvested earnings | 16,630 | 22,368 | 34.5 | 5,738 |

| Other flows | 7,205 | -3,061 | n/a | -10,266 |

| To the rest of the world | ||||

| Total net flows | 21,099 | 31,331 | 48.5 | 10,232 |

| Mergers and acquisitions | 6,188 | 20,018 | 223.5 | 13,830 |

| Reinvested earnings | 22,682 | 23,611 | 4.1 | 929 |

| Other flows | -7,774 | -12,297 | n/a | -4,523 |

| Sectors of CDIA outflows | ||||

| Energy and mining | -3,014 | 9,836 | n/a | 12,850 |

| Manufacturing | -3,558 | 6,889 | n/a | 10,447 |

| Trade and transportation | 56,571 | 17,893 | -68.4 | -38,678 |

| Finance and insurance | 28,310 | 24,935 | -11.9 | -3,375 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 9,439 | 6,215 | -34.2 | -3,224 |

| Other industries | 15,842 | -1,491 | n/a | -17,333 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 36-10-0025-01 and 36-10-0026-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

The stock of CDIA grew for the ninth consecutive year. Following last year’s gain of 5.6%, Canadian investors added $122 billion (+10%) to their direct investment holdings abroad to reach a record high of $1,289 billion in 2018, with CDIA stock in both North America and Europe posting double-digit growth.

By country, the United States continued to be Canadian investors’ number one destination, with a CDIA position of $595 billion, or 46%, of the overall CDIA stock at the end of 2018. The United Kingdom remained the second-largest destination, with the CDIA stock expanding by 12% to reach $109 billion; Luxembourg, Barbados and Bermuda rounded out the top five. The stock of Canadian investment in Asia and Oceania grew at a relatively slower rate, up 4.3% to $89 billion in 2018. CDIA in Australia contracted slightly, but the stock of investment in other top Asian destinations grew faster the 10% average, as China, Hong Kong SAR, and Japan all recorded double-digit growth rates. By comparison, Canadians decreased their investments in South and Central America and Africa, down 1.0% and 1.5%, respectively.

Canadian investors increased their direct investment holdings abroad in all sectors except information and culture (down $6.2 billion to $38 billion). CDIA in finance and insurance led all sectors, up $53 billion (or 13%) to $471 billion, with half of the increase in the United States. This sector comprised 37% of the overall stock of CDIA in 2018. The transportation and warehousing sector CDIA stock position posted the second-largest growth, up $18 billion to $84 billion in 2018. Other sectors that saw significant growth in their CDIA stock were management of companies and enterprises (+11%), mining and oil and gas extraction (+5.4%), and manufacturing (+11%).

| 2017 ($M) |

2018 ($M) |

Share 2017 (%) |

Share 2018 (%) |

Change (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All countries | 1,167,243 | 1,288,869 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 10.4 |

| North America | 719,020 | 807,734 | 61.6 | 62.7 | 12.3 |

| United States | 524,976 | 594,994 | 45.0 | 46.2 | 13.3 |

| Barbados | 56,027 | 64,824 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 15.7 |

| Bermuda | 45,461 | 47,007 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| Cayman Islands | 40,245 | 39,624 | 3.4 | 3.1 | -1.5 |

| Bahamas | 24,131 | 27,096 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 12.3 |

| Mexico | 19,534 | 22,495 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 15.2 |

| British Virgin Islands | 6,415 | 9,617 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 49.9 |

| Europe | 287,802 | 317,773 | 24.7 | 24.7 | 10.4 |

| United Kingdom | 97,611 | 109,331 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 12.0 |

| Luxembourg | 81,692 | 90,069 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 10.3 |

| Netherlands | 34,647 | 36,475 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 5.3 |

| Germany | 9,162 | 10,481 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 14.4 |

| Ireland | 9,200 | 9,969 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 8.4 |

| France | 6,743 | 7,395 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 9.7 |

| Asia and Oceania | 85,232 | 88,923 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 4.3 |

| Australia | 31,926 | 31,205 | 2.7 | 2.4 | -2.3 |

| China | 11,182 | 12,736 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 13.9 |

| Hong Kong SAR | 7,839 | 9,053 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 15.5 |

| Japan | 6,546 | 7,560 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 15.5 |

| South and Central America | 67,889 | 67,197 | 5.8 | 5.2 | -1.0 |

| Chile | 22,728 | 21,501 | 1.9 | 1.7 | -5.4 |

| Peru | 13,566 | 14,246 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 5.0 |

| Brazil | 14,006 | 14,119 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| Africa | 7,300 | 7,190 | 0.6 | 0.6 | -1.5 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0008-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019

| 2017 ($M) |

2018 ($M) |

Share 2017 (%) |

Share 2018 (%) |

Change (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, all industries | 1,167,243 | 1,288,869 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 10.4 |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 2,140 | 2,412 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 12.7 |

| Mining and oil and gas extraction | 184,758 | 194,727 | 15.8 | 15.1 | 5.4 |

| Utilities | 38,042 | 44,551 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 17.1 |

| Construction | 2,218 | 3,153 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 42.2 |

| Manufacturing | 93,444 | 103,271 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 10.5 |

| Wholesale trade | 23,279 | 25,316 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 8.8 |

| Retail trade | 12,752 | 13,060 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 2.4 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 66,816 | 84,460 | 5.7 | 6.6 | 26.4 |

| Information and cultural industries | 44,201 | 37,989 | 3.8 | 2.9 | -14.1 |

| Finance and insurance | 418,743 | 471,318 | 35.9 | 36.6 | 12.6 |

| Real estate, rental and leasing | 72,251 | 77,803 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 7.7 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 26,416 | 29,763 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 12.7 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 154,172 | 171,311 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 11.1 |

| Accommodation and food services | 3,343 | 3,595 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 7.5 |

| All other industries | 24,668 | 26,141 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 6.0 |

| Information and communication technologies (ICT) | 17,774 | 18,975 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 6.8 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0009-01; retrieved on 24-06-2019